Version 1.0 - May 2014

by Clint Rauscher and Shelley Brooks

The concept of this performance is to show a progression of Argentine Tango from its early days up to today, demonstrating different rhythms, embraces and styles. We also tried to work in the 4 primary orchestras of tango D’Arienzo, Di Sarli, Troilo and Pugliese.

Performance Notes: This is our first time attempting this performance. I finished editing the music on Thursday and we performed the very next night, at the Spoleto Tango weekend in Charleston, Sc. This performance is completely improvised, Shelley did not even know which songs I had decided on prior to the performance. Since this was our first time attempting this performance, we asked for feedback from the audience and got some great ideas. We ask the same from you, please provide us with any constructive criticism that you might have. We want to fine tune this concept and perform it again in the near future.

Chapter 1: Early Tango Criollo and Guardia Vieja (Old Guard) (1850s to 1925)

We did not include this period in our performance. The main reason is that we wanted to keep the performance around 10 minutes and we have not practiced this style of tango very often. We plan on adding it in our next iteration of the performance and will likely use:

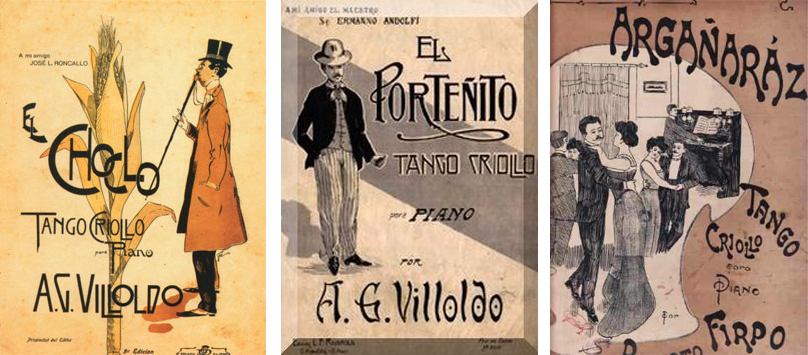

The reason for choosing this song is the recording quality, tempo and rhythm. I have many early recordings going all the way back to 1907, but the recording quality was very poor on most of these recordings. The earliest tangos, were actually habaneras mixed with European and African musical influences such as candombe and polka, etc. In the sheet music at the time you can see some of these songs being labeled tango-milongas, tango-habaneras or tango-criollo. This music was in 2/4 time and mostly spirited and light in nature. It was faster than the modern tango of today, but slower than today’s milonga.

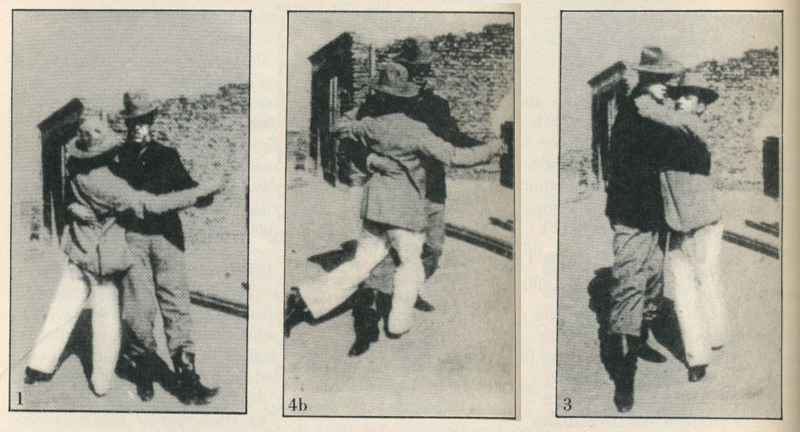

The earliest pictures that we have of tango are from 1903 and feature a well known dancer, and friend of Carlos Gardel, Arturo de Navas. In the pictures, he is dancing with another man and the dance is labelled “El Tango Criollo.” I would argue that there were many competing styles of tango during this period and that the general term Tango Criollo would have encompassed the styles of Tango Orillero and Canyengue.

Tango Orillero would have been more upright and the dancers would have danced in a more spirited and light manner. Canyengue would have been danced more down and with more attitude and swagger. Tango Liso would have also existed during this time and would have been a more calm and prim and proper way of dancing in the nicer dance halls. According to Carmencita Calderon, “It was always the dance hall on the one hand and the canyengue on the other.”

I think that Eduardo Arquimbau gives the best explanation of the difference between Tango Orillero and Canyengue in this video (jump to 57min 45sec mark and watch until he is done demonstrating the walk).

The primary orchestras of this period would be Aduardo Arolas, Roberto Firpo, Juan “Pacho” Maglio, Quinteto Criollo Atlanta, and Vincente Greco.

Chapter 2: Guardia Nueva (The New Guard) (1925 to 1935)

During this period, the habanera influence began to fade and the tempo of the music slowed down with the proliferation of "El Cuatro" or "The Four." "The four" consists of 4 equal quarter notes (beats) with 2 strong beats (down beats) and 2 weak beats (up beats). Along with the music slowing down, it also began to get more complex with the melodic structure having a stronger role.

This is where our performance begins. The song that we use in our performance is “Lorenzo” by Julio de Caro from 1926. I picked this song, because it has a classic rhythm of dance music from this period. Most of the music that people label as Guardia Vieja is actually music from the Guardia Neuva period being played in a Guardia Vieja style. This Guardia Vieja style was even used by Canaro’s Quinteto Pirincho in the 1940s and 1950s and by more modern orchestras like Los Tubatango in the 1960s and 1970s.

“Lorenzo” is a great example of how tango slowed down during this period and took on a more heavy feeling. It is still a very fun and playful song, but “Lorenzo” is more grounded than “Venus” and has more canyengue or swagger. Another important feature of this song is the use of the arrastre. You can clearly hear it for the first time in “Lorenzo” at the 45 second mark, it sounds like a stretch or drag and then a fall.

“Lorenzo” by Julio de Caro from 1926

Our dance in this section, is what I some would call Canyengue. To me, Canyengue is not a codified style but rather an attitude or expression. It is not an embrace or a particular set of steps. To dance Canyengue, you are dancing with a swagger and sway.

Again, we are dancing with an embrace which is often associated with Canyengue, where Shelley is oriented a little more to my right side. We are dancing cheek to cheek with our heads pointed in the same direction. Our knees are slightly bent and we bring the open side of the embrace down to the man's left hip. While this might very well have been an early embrace of tango, there are plenty of pictures from the early 1900s where people are standing perfectly upgright while dancing. In this part of hte performance we dance playfully, with lots of swagger and sway often using the quick-quick-slow rhythm. I would argue that that is what makes it Canyengue.

Dancing almost died out during the Guardia Nueva period, because the musicians began playing with the phrasing, harmony and the melody instead focusing on a steady beat. People were buying records and listening to tango on the radio and dancers were not the primary concern. Orchestras like De Caro's were creating a music that was more at home in a concert hall than a dance hall. A perfect example of this would be Julio de Caro’s “Flores Negras.” Imagine trying to dance to this when you were used to the very clear steady rhythms of the Guardia Vieja period. Even today, this would not be a song we would dance to.

“Flores Negras” by Julio de Caro from 1927

Chapter 3: The Return of the Milonga

We did not use this in our performance. We cut it for time, but based on feedback I plan to add it back in our next performance. In the 1800s, gauchos, Argentine cowboys, would often sing songs while someone would play a habanera rhythm on the guitar. These boastful songs were performed as contests and were often referred to as milongas.

Poem from the late 1800s:

"You gentlemen confessing milonga,

Let’s battle right here.

Smoke us, milonguero,

if you dare."

During the 1920s, Tango slowed down and the habanera/milonga rhythm disappeared. It did not return until the early 1930s, milonga was reborn with Sebastian Piana’s composition “Milonga Sentimental.”

“Milonga Sentimental” by Francisco Canaro from 1933

Chapter 4: The Golden Age of Tango (1935 to 1955)

Part 1: Rhythmic Tango

As mentioned above, tango for dancers almost died out dying the Guardia Nueva period. But in the 1930s, Juan d’Arienzo came along and started playing more rhythmic tangos reminiscent of the old style. D’Arienzo’s music was not simple but it had a very clear and steady beat which dancers loved.

For our second song, we dance to “Pénsalo Bien” by Juan d’Arienzo with Alberto Echagüe singing from 1938. We now take a more traditional embrace and stand up straight. To this music, we try to express the rhythm of the music by remaining very playful and making small staccato steps without a lot of long pauses or fancy steps. It is more about expressing the rhythm.

“Pénsalo Bien” by Juan d'Arienzo from 1938

Part 2: The Elegance of Tango Salon

To explore this elegant style of tango, I chose “La Capilla Blanca” by Carlos di Sarli with Alberto Podesta singing, from 1944. The music of Di Sarli had a clear, danceable rhythm while being complex enough for advanced dancers to enjoy. He respected both the melody and the rhythm of tango. When dancing to D’Arienzo, dancers often step on most every beat, but when dancing to Di Sarli it is common to dance very slowly and to dance to the melody as well as the underlying beat, employing dramatic pauses. When dancing Salon Tango, dancers will often dance in a mostly close embrace, while expanding their embrace for more complex figures.

“La Capilla Blanca” by Carlos di Sarli from 1944

Part 3: Milonga of the Golden Age

After milonga’s return in the 1930s, it continued to speed up. We represent change in tempo by dancing to Aníbal Troilo’s “Ficha de Oro” with Francisco Fiorentino singing, from 1942. The important thing in milonga is not fancy steps, but respecting the rhythm of the milonga. If you listen carefully to the music, you can still hear traces of the habanera in most modern milongas.

“Ficha de Oro” by Aníbal Troilo from 1942

Part 4: Vals (Waltz) of the Golden Age

Vals had been around since the beginning of the tango, but here we are dancing to a typical Golden Age vals “Pobre Flor” by Alfredo de Angelis with Carlos Dante and Julio Martel singing, from 1946. In our performance, we try to demonstrate the rhythm and flow of the vals.

“Pobre Flor” by Alfredo de Angelis from 1946

It should be noted that there are many sub-styles of Tango-Vals to explore.

Part 5: Dramatic Tango of Osvaldo Pugliese

To fully understand, we must revisit our conversation about the Guardia Nueva period. Pugliese composed his first tango “Recuerdo” in 1924, when he was only 19 years old. “Recuerdo” was one of the most important compositions of the Guardia Nueva period. In this first composition, Pugliese revealed a revolutionary, polished structure. While one can dance to "Recuerdo," imagine what a departure it was from the simple music that went before it. Here is what Horacio Ferrer had to say, "One could speak, with total justice, of compositions before and after Pugliese's "Recuerdo" and the instrumentalists before and after "Recuerdo." The revolutionary conductor and composer Julio de Caro recorded it first in 1926.

“Recuerdo” by Julio de Caro from 1926

We picked his song “Chiqué” from 1953, to demonstrate this more dramatic form of tango. While his music is often associated with performance tango, he was an incredibly popular orchestra during the Golden Age and much respected by accomplished dancers. One of the reasons that we picked “Chiqué” was that it contains all the signature elements that make Pugliese’s music so special, at some moments it is soft and delicate and then bold and dramatic.

“Chiqué” by Osvaldo Pugliese from 1953

Chapter 5: Modern & Electronic Tango

In the final song, we chose “Los Vino” by Otros Aires, from 2007, to represent modern electronic tango. One reason that we picked this song is that it has a rhythm similar to the first song that we danced to. In fact, we start off “Los Vino” with the same steps that we used to start “Lorenzo.” You might also notice that the lyrics reference 3 of the orchestras that we danced to in the the performance Pugliese, Troilo and D’Arienzo.

In our performance, we tried to show some of the more modern steps of tango such as soltadas, volcadas and colgadas.

“Los Vino” by Otros Aires from 2007

Notes on the Performance

As I stated at the beginning, we appreciate any constructive criticism: clint@tangology101.com. If it is of a historical nature, please provide sources for me to review. We were concerned about the time of the performance, but no one complained about that. In fact, the main complaint was that they wanted more information. They wanted us to stop between each song and give a brief explanation. I am going to try to do this next time.

Again, this was the first time we ever attempted it and did not even rehearse before hand, but in the future I want to have some specific figures to work in to each period that are more representative of that period. I have a few more canyengue steps that I would like to work in and some enrosques, planeos and sacadas for the Tango Salon portion.

We also have an idea of just doing a performance that shows the history of just tango from the Golden Age.