In order to better understand why D'Arienzo was such a big deal, we have to look at what was going on in regards to tango at that time.

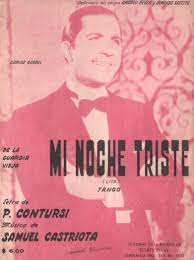

In 1917, Carlos Gardel releases a song called "Mi Noche Triste (My Sad Night)," written by Pascal Contursi. As Enrique Santos Discépolo, a tango lyricist and contemporary of Contursi, put it, this was the event that moved tango "from the feet to the mouth."1 "Mi Noche Triste" was "the first tango designed to be sung and not danced."2 There had been tangos with lyrics for some time, but those songs were usually upbeat and described some colorful character like "La Morocha" or "Don Juan." Now tango was telling a full story and trying to illicit an emotional response. Also, the singer sang from the beginning to the end of the song. The singer was the star and the lyrics were more important than the music. This style of tango became increasingly popular in the 20s and 30s and was known as "Tango Canción." This music was intended to be played on record players and listened to, not danced to.

In 1917, Carlos Gardel releases a song called "Mi Noche Triste (My Sad Night)," written by Pascal Contursi. As Enrique Santos Discépolo, a tango lyricist and contemporary of Contursi, put it, this was the event that moved tango "from the feet to the mouth."1 "Mi Noche Triste" was "the first tango designed to be sung and not danced."2 There had been tangos with lyrics for some time, but those songs were usually upbeat and described some colorful character like "La Morocha" or "Don Juan." Now tango was telling a full story and trying to illicit an emotional response. Also, the singer sang from the beginning to the end of the song. The singer was the star and the lyrics were more important than the music. This style of tango became increasingly popular in the 20s and 30s and was known as "Tango Canción." This music was intended to be played on record players and listened to, not danced to.

Before the mid-1910s, tango music was almost always played in the more upbeat 2/4 time signature with a habanera-like rhythm. If you counted out 8 whole beats it would have looked like this: ONE two three FOUR FIVE six SEVEN eight or Duum Da Dum Dum (Capitalized words equal the stronger beats). The sheet music from this period was often labelled Milonga, Tango-Milonga, or even, Tango Criollo. You can hear this in the song below, "Venus" by Juan Maglio, from 1912.

You can also hear this in the first version of the famous, "La Cumparsita" recorded by Roberto Firpo, in 1916.

In the 1920s, a new group of musicians emerged that were more classically trained than those of the previous generations, who were largely self-taught. They were more avante-guard, focusing on robust, complex arrangements and a slower tempo, than that of the Guardia Vieja (Old Guard) period. By the mid-1920s, a new period of tango had emerged called the Guardia Nueva (New Guard) which saw the birth of the 'evolutionary' school of tango.

This split tango into two schools, each with its own musical structure and style: The 'evolutionary' school (De Caro School) and the 'traditional' school (Canaro School). The 'evolutionary' school included the orchestras of Julio de Caro, Osvaldo Fresedo, Juan Carlos Cobián, Pedro Maffia, and Cayetano Puglisi. While the 'traditional' school consisted of Francisco Canaro, Roberto Firpo, Francisco Lomuto, Anselmo Aieta, and Edgardo Donato. "The 'traditional' school stressed the beat, and produced an infinitely more danceable tango."4 Some of the older generation would say, in reference to the evolutionary school, "They have turned tango into church music," because they were working more with melody and harmony.

Also, by the 1920s, the guitar and flute had all but disappeared, being completely replaced by bandoneones, pianos and the double bass. This new instrumentation allowed for more complex arrangements and slowed tango down even further. Composers began writing tangos in 4/4 time ("The Four") or 4 notes, equal in length, per measure. This might be expressed as: ONE two THREE four.3 To understand this, let's listen to "La Cumparsita" played in 4/4 time by the same orchestra, Roberto Firpo, in 1928. Notice that the tempo has changed, it is much slower. Clearly Firpo has been feeling the influence of the Guardia Nueva movement. This arrangement is far more complex and is even using pizzicato (plucking of the violin strings) and arrastres (drags on the bass).

And finally, here is an example of a typical song from the leader of the Guardia Nueva movement, Julio de Caro, called "Flores Negras," from 1927. As you can hear, it is very complicated and with no clear rhythmic beat for dancing. It is beautiful music and great for listening, but not at all for dancing tango.

Both of these movements, the Tango Cancíon and the 'evolutionary' movement, diminished the importance of making music for the dancers. Tango historian, José Gobello has written, "The dance had become subsidiary... displaced by lyrics and the singers, and now it is displaced by the arrangement."5 Many orchestras were more concerned about playing in the theaters, on the radio, and selling records. Tango dancing did not "die" during this time, and there were still some orchestras playing music suitable for dancing, but the number of people dancing did sharply decline during this period and few new dancers were starting. This was what was happening just before the "D'Arienzo Revolution" took place.

1 Jiménez, Francisco García, Carlos Gardel y Su Época, Buenos Aires: Esiciones Corregidor, 1976, p. 175.

2 Castro, Donald S., The Argentine Tango as Social History (1880-1955): The Soul of the People, The Edwin Mellen Press, Ltd., 1991, p. 164.

3 Lavocah, Michael, Tango Stories: Musical Secrets, Milonga Press, 2012, p. 8. (description of the difference between 2/4, 4/8, and 4/4 time)

4 Collier, Cooper, Azzi, Martin, Tango!: The Dance, the Song, the Story, Thames and Hudson, 1995, p. 119.

5 Gobello, José, Juan D'Arienzo, Todo Tango, viewed on 05/11/18.