Rhythm vs Melody

The rhythm of a song is the basic beat, "pulse," or steady flow of the music. The rhythm is what you would clap your hands to or change weight to as you listen to a piece of music.

The melody or melodic rhythm is the "wave" of the music or what you would hum. Melody would consist of the shape, movement and intensity of the notes to one another.

Usually, the rythm is played by the accompaniment consisting of piano, double base and one bandoneon while the rest of the instruments play the melody or solos. You might have two melodies playing at the same time, overlapping each other, such as two bandoneons playing different melodies. Also, melodies will often repeat, with variations, throughout the song.

The rhythm would be each individual sound, while the melody is the wave-form of those sounds. If you just listen to a single measure, you will not hear the melody. If you listen to a phrase then you will hear the melody. The melody might last from anywhere from one phrase (see below) to a whole section of the song. Melody is not just about the notes played, but HOW they are played and where the accents are placed.

Dancer's Note: Imagine the rhythm as being a steady base that lies underneath with the melody floating on top.

As dancers, we want to be aware of both the rhythm and the melody. We can dance to either one, but the mark of an advanced dancer is being able to hear which is dominant and be able to adapt their dance accordingly. If both are equal, then it is up to the leader.

Also, you want to hear the flow of the melody, so that you can hear the melodic accents and climaxes in the music. These accents will often correspond to a beat of the rhythm. If we are dancing to the melody, this when we want to step or perform a boleo or gancho. The accents can be placed on any beat, but almost always on the first beat of a measure. You don't necessarily have to "know" the song by heart to hear these accents coming. Since tangos often repeat themselves, if we pay attention to the first verse and to the first chorus then we should have a good idea of where the accents are going to be for the rest of the song. I say a good idea, because often accents do change from section to section.

Measures

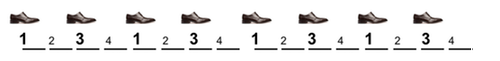

Tango music is in 4/4 time (4 beats per measure), two upbeats and two downbeats (strong). In the graphic below, 1 is a downbeat, 2 is an upbeat, 3 is a downbeat and 4 is an upbeat. Dancer's Note: As tango dancer's we first learn to step in "single-time," which means to walk on the downbeats, so we step on the 1 and the 3. Then we learn double-time, half-time and syncopation. To dance just in single-time would be very boring. We will look at these other times the article Musicality 101.

One measure in 4/4 time:

Phrases

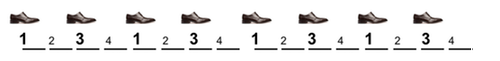

Each of the 5 sections of a tango are made up of 4 phrases. A phrase consists of 4 measures or 8 single-time beats, so each section has 32 sing-time beats.

One phrase in 4/4 time:

One Section (Four Phrases):

Exercise: Let's listen to "Que Nunca Me Falte" by Ricardo Tanturi. In this song, you can clearly hear the ending of each phrase. You will notice that each phrase ends on the seventh walking (strong) beat and that the eight is silent. Then the next phrase begins with a strong 1.

Deeper into Phrases

The understanding of phrasing is one of the most important aspects to good musicality. I like to think of a tango as a story, each section as a paragraph, each phrase as a sentence and each beat as a word. While words (beats) do convey meaning, the sentence (phrase) is really the most important thing to express.

These sentences can convey a simple statement, exclaim strong emotion or can even ask a question. My favorite way of thinking of a section of tango music is that there is a question and then an answer (call and response). This can take many forms. The first phrase might be a question which then gets answered by phrase 2.

Let's listen to the first two phrases of "Bahía Blanca:"

Phrase 1 & 2 of "Bahía Blanca:"

Phrase 3 & 4 of "Bahía Blanca:"

I like to think that the first two phrases are a statement or question and that the last two phrases are a sharp response. You can even hear Di Sarli putting a period or exclamation mark at the end of the last phrase with the piano "ping." The last phrase of a section usually ends more dramatically with some sort of strong punctuation to let you know that the section is over and that a new section is beginning.

Dancer's Note: In my opinion, being able to hear the ebb and flow of the phrases and the resolution of phrases is one of the most important concepts to understand about the music. Notice if the phrases are flowing together or if each phrase is ending in a strong period or comma (pause) and exploit that knowledge in your dance. It is especially important to be able to hear the end of the final phrase of any section, as those mark crucial transitions within the song.

The end of sections, is where we want to pause or end an idea such as a turn or sequence. It is SUPER important not to "blur" the end of a section, if there is a pause in the music. Imagine that at the end of a section is a red light, which you need to acknowledge. The first beat of the next section is your "green light" to move again.

The Outro or Coda (tail)

The outro is usually the final verse of the song. It is usually very similar to the first two verses, but will often include an instrumental solo or some slightly different instrumentation. Often the outro will gain in energy leading up to the final chum-chum. Listen to the Outro (Verse 3) of "Pensalo Bien" and notice the bandoneón solo runs.

"Pensalo Bien" Verse 3

Chum-Chum

The final two notes of a tango are often referred to as chum-chum. Many orchestras put their own unique stamp on the chum-chum.

End of "Al Compas del Corazon" by Miguel Caló

Strong first chum -- pause -- soft piano notes for second chum

End of "Llorar Por Una Mujer" by Enrique Rodriguez

Rodriguez probably has the most famous ends, because he would only do the first chum and then skip the second chum.

End of "La Yumba" by Osvaldo Pugliese

Strong first chum -- pause -- Soft second chum

End of "La Vide Es Corta" by Ricardo Tanturi

Strong first chum -- pause -- piano note for second chum