In 1935, D'Arienzo enters the recording studio and returns to the faster, stronger rhythm of the Guardia Vieja and helps usher in the Epoca de Oro (The Golden Age). According to bassist, Pablo Aslan, "D'Arienzo got his punch more from staccato than with arrastre,"1 assocaiting staccato with the 'traditional' school and arrastre with the 'evolutionary' school.

D'Arienzo retuned to the hard driving 2/4 tempo of the Old Guard, but without the habanera rhythm of the Old Guard.

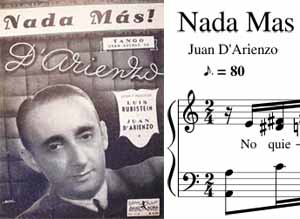

Some have said that what D'Arienzo was techically doing was in a 4/8 timing, which is a more complex version of 2/4.1 But D'Arienzo used the 2/4 time signature in his sheet music, and used the 2/4 designation in interviews, "If the musicians return to the purity of 2/4, it will revive the enthusiasm for our music." So, I will leave it to the music experts to debate this.

Some have said that what D'Arienzo was techically doing was in a 4/8 timing, which is a more complex version of 2/4.1 But D'Arienzo used the 2/4 time signature in his sheet music, and used the 2/4 designation in interviews, "If the musicians return to the purity of 2/4, it will revive the enthusiasm for our music." So, I will leave it to the music experts to debate this.

The way that I describe D'Arienzo's rhythm/timing for dancers is as: ONE and TWO and THREE and FOUR. In other words, you have a primary pulse (strong beat) and a sub-pulse (the "ands"). Of course, all tango has a sub-pulse, but D'Arienzo's sub-pulse is stronger than in most tango music, and dancers will find themselves wanting to use a lot of the "ands." This is what drives people to the dance floor and makes them want to dance. They can simply step on the primary pulses or they can double-time by using the "ands/sub-pulses," giving the dancers lots of variations to chose from. Of course, we do this with pretty much all tango music, but in the case of D'Arienzo, it almost feels wrong not to use lots of double timing. The increased tempo and the stronger sub-pulse is also why some dancers mistake some tangos by D'Arienzo as milongas, but milongas have a particular rhythm.

The rhythm of D'Arienzo's 2/4 was more steady and equal than that of the Old Guard. His up-tempo sound consisted of a solid, steady march forward, that was clear and easy for dancers to interpret. Of course, all music has melody, but that was not the primary focus of D'Arienzo's music. His focus was on producing an up-tempo beat. Also, his tangos rarely drag notes (arrastre) or hold them for long dramatic pauses like the 4/4 of the Guardia Nueva. He was working somewhere between the Old Guard and the New Guard.

To hear this, let's listen to the same song, "Jueves," recorded by Julio de Caro in 1930 and the Juan D'Arienzo's version from 1937.

I think it is easy to hear why dancers responded so favorably to D'Arienzo. De Caro's might be more complicated for a listening audience, but the rhythm in his version seems to get lost, while D'Arienzo's rhythm is clear and distinct.

In later years, D'Arienzo would comment on the 'evolutionary' school, by writing:

"In 1937 there were gentleman directors in the lineup: Osvaldo Fresedo, Julio de Caro; but the tango was completely un-memorable. Then I played at a different beat and returned [tango] to the place it deserved."

"Young people like me. They like my tangos because they are rhythmic, nervous up-tempos. Youth is after that: happiness, movement. If you play for them a melodic tango and out of beat, surely they won't like it. That's what happens. Now there are good musicians and great orchestras that think that what they play is tango. But it is not so. If they don't have timing there's no tango. They think they can make popular a new style and perhaps they can be lucky, but I keep on thinking that if there is no beat there is no tango. As professionals I have respect for them all. But what they dig is not tango."2

Also, on the Tango Cancíon movement:

"In my point of view, tango is, above all, rhythm, nerve, strength and character. Early tango, that of the old stream (guardia vieja), had all that, and we must try not to ever lose it. Because we forgot that, Argentine tango entered into a crisis some years ago. Putting aside modesty, I did all was possible to make it reappear. In my opinion, a good part of the blame for tango decline is on the singers. There was a time when a tango orchestra was nothing else but a mere pretext for the singers. The players, including the leader, were no more than accompanists of a somewhat popular star…

Furthermore, I tried to rescue for tango its masculine strength, which it had been losing through successive circumstances. In that way in my interpretations I stamped the rhythm, the nerve, the strength and the character which distinguished it in the music world."2

From these two quotes, you can clearly tell how he felt about these movements, and also, what a modest person he was ;-). He once said, "With me one hundred thousand tango orchestras and neighborhood clubs flourished."3

Of course, D'Arienzo did work with many great singers such as Carlos Dante, Walter Cabral, Alberto, Reynal, Hector Maure, Alberto Echagüe, Armando Laborde, Jorge Valdez, and Libertad Lamarque. But, in general, the singers in his orchestra were at the service of the orchestra, not the other way around. The singers were used as another instrument, not the stars of the show.

And sometimes he even put them out front. He also made himself somewhat of a star and loved to enthusiastically direct the orchestra during live performances.D'Arienzo said of his direction:

"When I direct I am justifiably natural. And I transform. As I direct I take what I feel. Simultaneously I pass on my feelings to the musicians and they, to the public... Before I directed with the baton, now with my own hands: they are more expressive.

Do not think that this is just for the public to see - it is used as a defence by me. I use it well. A look implies a mistake by someone, something that is not played well. They are used by me as a course when I see a loose element, or someone is distracted. I encourage and demand that you be aware, and encourage you with enthusiasm."3

Below is a video showing D'Arienzo directing his orchestra:

Of course, not everyone liked D'Arienzo's style. Many of the devotees of Tango Cancíon, and especially the De Caro school, saw this turn back to the strong beat, as regressive for tango music. But the dancer's loved it, and between 1935 and 1939, he recorded 116 sides, selling more than Canaro and Troilo combined. In fact, his records were so popular that people were buying little else, and some record stores began requiring customers to buy something else, in order to by one of his records.4

Unfortunately, no masters from that period remain. Everything we listen to today are recordings of 78s and LPs.5

D'Arienzo and Biagi

A defining moment of D'Arienzo's career came in 1935, when he added pianist, Rodolfo Biagi, to his orchestra. Biagi had just returned from working overseas and D'Arienzo had grown tired of Fasoli showing up late.

Together D'Arienzo and Biagi created his signature driving staccato sound. Soon after, Biagi began writing new arrangements of the songs, creating an even more staccato, up-tempo sound than that of the Guardia Vieja. They also increased the typical number of violins and bandoneons to five each. This filled the songs with an unparalled, aggressive energy that dancers and listeners loved. Let's listen to their first recording together "Nueve de Julio."

"Nueve de Julio" by Juan D'Arienzo (1935)

In 1936, "El Vasco Aín acted in the show, La Evolución del Tango that Julio de Caro presented at the Teatro Opera, and Pablo Osvaldo Valle, artistic director of Radio El Mundo, brought D'Arienzo and his orchestra to the radio, with the splendid incorporation of Rodolfo Biagi. The quick beat and vibrant temperament that the young pianist instilled created such a well-defined rhythmic profile that it paved the way for the tango dance explosion in the following decade."9

In 1936, "El Vasco Aín acted in the show, La Evolución del Tango that Julio de Caro presented at the Teatro Opera, and Pablo Osvaldo Valle, artistic director of Radio El Mundo, brought D'Arienzo and his orchestra to the radio, with the splendid incorporation of Rodolfo Biagi. The quick beat and vibrant temperament that the young pianist instilled created such a well-defined rhythmic profile that it paved the way for the tango dance explosion in the following decade."9

Dancer, "El Loco" Márquez, would say: "D'Arienzo was everything to me. As soon as I heard him, I took up the tango that I had left behind at 17, bored from dancing to Francisco Canaro and Villoldo... for me tango has always been something happy. It hurt me when they tried to make something sad out of tango. I had a happy style."9

Ok, so a style is developing, but what makes Biagi so special, as a piano player? Why was he given the nickname "Manos Brujas" (Witchy/Magical Hands)? Let's listen to another song from two years later, their interpretation of the seminal piece "El Choclo." Here, we will hear his magical hands at work connecting the phrases and adding little accents.

"El Choclo" by Juan D'Arienzo (1937)

The picture above is of D'Arienzo (5th from right) and his Orchestra, including Biagi (4th from right) at the Chantecler Club in 1937.

The picture above is of D'Arienzo (5th from right) and his Orchestra, including Biagi (4th from right) at the Chantecler Club in 1937.

By 1938, D'Arienzo's orchestra was at the height of its popularity. He was just 35 years old, one less than Julio de Caro, but stylistically at the other end of the musical spectrum of tango. His records were selling and his orchestra was regularly playing on the radio. But remember, when I made the joke above about D'Arienzo being modest? Well, audiences had been becoming bigger and bigger fans of Biagi, and at a concert later that year, after a performance of “Lágrimas and Sonrisas,” the audience clapped until Biagi finally stood up and took a bow. As the story goes, D'Arienzo walked over to him and whispered in Biagi's ear, “I’m the only star of this orchestra. You’re fired.”6

"Lagrimas y Sonrisas" by Juan D'Arienzo (1936)

Some doubt this story surrounding Biagi's firing, and it very well may not be true, but I do find it interesting that Biagi recorded a far superior version of "Lágrimas y Sonrisas" three years later, featuring some "standing ovation" worthy piano playing.

"Lagrimas y Sonrisas" by Rodolfo Biagi (1941)

Regardless, of how they split, we will always have the 66 tangos that they recorded together including my favorites: "El Flete," "La Payanca," "Rawson," "Ataniche," "Que Noche," "El Porteñito," "El Cencerro," "La Cumparsita," "El Africano," "Melodía Porteña," "Pénsalo Bién," and "Champagne Tango."

And, lucky for us, this split did not seem to slow either of them down, so maybe the split was mutual and already in the works. In just two short months, Biagi put together a full orchestra and signed a record contract, and a radio contract. D'Arienzo replaced Biagi with Juan Polito, and was back in the recording studio just two weeks later.

Juan Polito

With the amazing pianist, Juan Polito, D'Arienzo continued down the path that he and Biagi had started. I feel that Polito is underrated and his piano playing is exceptional. D'Arienzo and Polito recorded 40 songs together, many of which are favorites of mine, including: "Nada Más," "La Bruja," "Ansiedad," "No Mientas," "Derecho Viejo," "Mandria," and "Trago Amargo."

Alberto Echagüe

Echagüe began recording with D'Arienzo's orchestra in April of 1938, when Biagi was still in the orchestra. But he had been performing with the orchestra, at least since 1937, because he was featured singing "Melodia Porteña," with D'Arienzo in the feature film of the same name. It is odd though, that D'Arienzo recorded "Melodia Porteña," in December of 1937, as an instrumental.

Echagüe was not considered an elegant singer, but rather, he possessed a tough guy style of singing, which was a perfect fit for the aggressive, hard driving sound of D'Arienzo and Biagi. He was often compared to Ángel Vargas, with whom he shared a similar phrasing and canyengue style. Canyengue is often used to describe a streetwise attitude or persona. Echagüe was introduced to D'Arienzo by Ángel D'Agostino, who's orchestra he was singing with at the time.7

Echagüe, like the other singers that worked with D'Arienzo, was used as an estribillista or chansonnier (singer of the refrain). An estribillista would only sing a small portion of the lyrics of a song, usually the chorus towards the end. This was in contrast to the soloist, who would sing the whole song, such as in the Tango Cancíon, where the music took second place. An estribillista was not the "star" of the orchestra, but used as another instrument, equal to the others.

Echagüe and D'Arienzo would work together, off and on, from 1938 to 1975, recording over 130 songs. During this first period, they recorded 27 songs together, starting with “Indiferencia,” on January 4, 1938 and ending with “Trago Amargo,” on December 22, 1939. During this period they would record such dancing standards as: "Pénsalo Bién," "Nada Mas," "La Bruja," "Ansiedad," "No Mientas," "Olvídame," "Mandria," "El Vino Triste," "Santa Milonguita," "Que Importa," and "Trago Amargo."

The Crash

This perfect combination of talent came crashing to a halt when, in early 1940, Juan Polito split with D'Arienzo, taking his entire orchestra with him, including Alberto Echagüe. But, as usual, D'Arienzo barely takes a breathe and is back recording with a new orchestra in just 4 months.

The Music

Below is my list of his most important music released during this time period, with some notes and links to lyrics. It is actually staggering how much "quality" music D'Arienzo produced during this short period, including valses and milongas. Most orchestras released primarily tangos with a handful of valses and milongas, but D'Arienzo put out so many amazing ones that we still listen and dance to today.

| Genre (Year) | Singer(s) | Title | Piano | Purchase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tango 1935 |

Sábado Inglés |

Lidio Fasoi |

| |

| Tango 1935 |

Joaquina |

Lidio Fasoi |  | |

| Tango 1935 |

Nueve De Julio |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| "Nueve de Julio" was the first song recorded with Rodolfo Biagi on Piano. The song title refers to the date of the Argentine Declaration of Independence. | ||||

| Tango 1935 |

Retintín |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1936 |

El Flete |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| In this context, "El Flete" translates to racehorse. Horse racing was a very popular sport in Buenos Aires. Carlos Gardel even owned his own racehorse. This is one of my favorite tangos to dance to and is probably the most perfect example of D'Arienzo's sound from this period. | ||||

| Tango 1936 |

La Payanca |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1936 |

Rawson |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1936 |

Don Juan |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1936 |

Ataniche |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1936 |

La Viruta |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1937 |

Qué Noche |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1937 |

El Choclo |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1937 |

El Porteñito |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1937 |

|

Paciencia |

Rodolfo Biagi |

|

| Another one of my all-time favorite tangos, and it was composed by D'Arienzo with lyrics by Francisco Gorrindo. He would later re-record this with Alberto Echagüe singing, in 1951. I love both version, but this is my favorite. (lyrics). | ||||

| Tango 1937 |

Jueves |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Not the most exciting song, but we often use this in our beginner classes, because it has a very clear and consistent rhythm. | ||||

| Tango 1937 |

El Cencerro |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Another one of my favorites. I love the flow of this song. | ||||

| Tango 1937 |

La Cumparsita |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1937 |

El Africano |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1937 |

Melodia Porteña |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Another song good for beginners. | ||||

| Tango 1938 |

Indiferencia |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| "Indiferencia" is the first song recorded with Alberto Echagüe and was composed by Biagi. (lyrics). | ||||

| Tango 1938 |

Rodriguez Peña |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1938 |

Unión Cívica |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1938 |

Pensalo Bien |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| "Pensalo Bien" is another all-time favorite and, I believe, one of Echagüe's greatest vocal achievements. (lyrics) Here is a video of Shelley and I dancing to Pensalo Bien: | ||||

| Tango 1938 |

Champagne Tango |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Tango 1938 |

El Internado |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1938 |

Nada Más |

Juan Polito |

| |

| "Nada Más" is another stunning tango composed by Juan D'Arienzo with lyrics by Luis Rubistein. I also love the singing by Echagüe and the piano by Juan Polito. (lyrics) | ||||

| Tango 1938 |

Florida |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1938 |

La Bruja |

Juan Polito |

| |

| And yet another favorite, but this time it is composed by Juan Polito, who also played piano on it, with lyrics by Francisco Gorrindo. (lyrics) | ||||

| Tango 1938 |

Ansiedad |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1938 |

No Mientas |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1939 |

Yunta Brava |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1939 |

Maipo |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1939 |

Olvídame |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1939 |

Derecho Viejo |

Juan Polito |

| |

| "Derecho Viejo" is a fairly dramatic song, and what I think is great about it is that every muscical instrument gets to shine, even the double bass gets its moment. | ||||

| Tango 1939 |

Mandria |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1939 |

Felicia |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1939 |

El Vino Triste | Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1939 |

Santa Milonguita |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1939 |

Qué Importa |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Milonga 1939 |

La Cicatriz |

Juan Polito |  | |

| Tango 1939 |

Pampa |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1939 |

Que Dios Te Ayude |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1939 |

Por Que Razón |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Tango 1939 |

Trago Amargo |

Juan Polito |

|

|

| "Trago Amargo" is another amazing song that is perfect for Alberto Echagüe to sing. It matches his canyengue style like a glove. At one point, it almost sounds like the piano and Echagüe are fighting for attention or having a heated discussion, as the piano is being played boldly over the singer. (lyrics) | ||||

| Genre (Year) | Singer(s) | Title | Piano | Purchase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vals 1935 |

Desde El Alma | Lidio Fasoli |

| |

| Vals 1935 |

Francia |

Lidio Fasoli |

| |

| Milonga 1935 |

De Pura Cepa |

Lidio Fasoli |

| |

| This is one of D'Arienzo's most popular milongas. | ||||

| Vals 1935 |

Pabellón De Las Rosas | Lidio Fasoli |

| |

This is D'Arienzo's version of a very famous and much recorded Vals (waltz) written by bandoneonist José Felipetti. It was first recorded by Arolas in 1913. It was written as a tribute to the Pavilion of Roses, a popular cabaret and dance hall, located in the Recoleta neighborhood of Buenos Aires. It was a very popular place for dancing tango, until it was torn down in 1929. This is D'Arienzo's version of a very famous and much recorded Vals (waltz) written by bandoneonist José Felipetti. It was first recorded by Arolas in 1913. It was written as a tribute to the Pavilion of Roses, a popular cabaret and dance hall, located in the Recoleta neighborhood of Buenos Aires. It was a very popular place for dancing tango, until it was torn down in 1929. |

||||

| Vals 1935 |

Orillas Del Plata | Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Super fun vals | ||||

| Milonga 1936 |

Silueta Porteña |

Rodolfo Biagi |  | |

| Vals 1936 |

Sueño Florido |

Rodolfo Biagi |  | |

| And another great vals | ||||

| Vals 1936 |

Un Placer |

Rodolfo Biagi |  | |

| Vals 1936 |

Tu Olvido |

Rodolfo Biagi |  | |

| Vals 1936 |

No Llores Madre |

Rodolfo Biagi |  | |

| Vals 1936 |

Inolvidable |

Rodolfo Biagi |  | |

| Vals 1936 |

Amor Y Celo |

Rodolfo Biagi | ||

| One of my favorite vals | ||||

| Vals 1936 |

Lágrimas Y Sonrisas |

Rodolfo Biagi |  | |

| Vals 1936 |

Una Lágrima |

Rodolfo Biagi |  | |

| Vals 1936 |

Corazón De Artista |

Rodolfo Biagi |  | |

| Vals 1936 |

Visión Celeste |

Rodolfo Biagi |  | |

| Vals 1937 |

Mentías |

Rodolfo Biagi | ||

| Milonga 1937 |

La Puñalada |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Not my favorite, but a classic that most everyone loves | ||||

| Vals 1937 |

Pasión |

Rodolfo Biagi |  | |

| Vals 1937 |

Valsecito Criollo |

Rodolfo Biagi |  | |

| Another classic | ||||

| Vals 1937 |

Valsecito De Antes |

Rodolfo Biagi |  | |

| Milonga 1937 |

Milonga Vieja Milonga |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Classic milonga | ||||

| Vals 1938 |

El Aeroplano |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Milonga 1938 |

Milonga Del Corazón |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Fast and fun milonga | ||||

| Milonga 1938 |

El Temblor |

Rodolfo Biagi |

| |

| Milonga 1938 |

Estampa De Varón |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Vals 1938 |

En Tu Corazón |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Vals 1938 |

Cabeza De Novia |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Milonga 1938 |

Milonga Querida |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Classic spirited milonga | ||||

| Vals 1939 |

Recuerdos De La Pampa |

Juan Polito |

| |

| Milonga 1939 |

Milonga Del Recuerdo | Juan Polito |

| |

| Vals 1939 |

Castigo | Juan Polito |

| |

| Milonga 1939 |

De Antaño | Juan Polito |  | |

| Milonga 1939 |

La Cicatriz | Juan Polito |  | |

| Vals 1939 |

Ay Aurora | Juan Polito |

|

|

1 Lavocah, Michael, Tango Stories: Musical Secrets, Milonga Press, 2012, p. 8.

2 D'Arienzo, Juan, Tango Has Three Things, Todo Tango, viewed on 05/14/18.

3 Juan D'Arienzo Biography, Very Tango Store, viewed on 05/11/18.

4 Lavocah, Michael, Tango Stories: Musical Secrets, Milonga Press, 2012, p. 9.

5 Lavocah, Michael, Tango Stories: Musical Secrets, Milonga Press, 2012, p. 12.

6 Comments Page, Tango and Chaos, viewed on 5/17/18.

7 Blaya, Ricardo García, Alberto Echagüe Biography, Todo Tango, viewed on 5/18/18.

8 Chantecler, Tango Thread, viewed on 6/8/19.

9 Benzecry Sabá, Gustavo The Quest for the Embrace: The History of Tango Dance 1800-1983, Abrazos, 2019, p.91-92.