I often get asked about dancing to tangos with singers. The tango singer has had four distinctive roles over time:

- National Singer (Cantor Nacional)

- The Refrain Singer (Estbrillista)

- The Orchestra Singer (Cantor de la Orchesta)

- The Star Soloist

These roles are not tied to specific dates, and they often overlapped in time.

Why is this important for dancers and DJs? The role of the singer impacts the structure of the music. Understanding this structure can help us as dancers. For DJs, we should understand which tangos are meant for and are good for dancing. The tangos best for dancing are the ones which utilize the singer as estribillista or as cantor de la orchesta. I will explain why.

The National Singer (Cantor Nacional)

From the earliest days of tangos, singers would accompany guitarists (sometimes pianos) or “typical trios.” They would sing all the lyrics of a song including verses and choruses (refrain). These duos or groups would usually play tangos, valses, and milongas, along with folk songs such as zambas, rancheras, tonadas. These singers were called “cantor nacional,” and they would be able to sing in all of these styles. Below is an example of a typical tango duo Corsini y Magaldi with Ignacio Corsini singing and Agustin Magaldi on guitar. Notice that Corsini sings the full lyrics: verse, chorus, verse, chorus.

"Palomita Blanca" by Ignacio Corsini (singer) & Agustin Magaldi (guitar)

This type of singer would also be employed for the tango canción. These were songs that were not intended for dancing and were mostly sentimental in nature. The most famous tango canción was probably "Mi Noche Triste (My Sad Night)" recorded in 1917 by Carlos Gardel.

"Mi Noche Triste" by Carlos Gardel (1917)

Some of the famous "cantors nacional" were Carlos Gardel, Ignacio Corsini, Hugo del Carril, Charlo, Agustín Magaldi, Alberto Gómez and Agustín Irusta.

The Refrain Singer (Estribillista)

When the orquesta típica was created in the early 1900s, they primarily played instrumentals. Sometimes a member of the orchestra might say something, but it was usually for humorous effect rather than singing. In his memoirs, Francisco Canaro claims that he was the first to use an estribillista in his orchestra. In 1927, he recorded his brother’s tango “Así es el Mundo,” which featured Roberto Díaz. Unfortunately, I have not yet been able to find a copy of this song.

So what defines an estribillista? An estribillista was restricted to singing a very small portion of the lyrics, usually the chorus (refrain) or just a single verse. They were considered just another instrument and were often not even mentioned on the record label and if they were then it was in very small type. Sometimes they were employed by a specific orchestra, but often they were employed by the recording label and would sing for all the orchestras under that label.

Some important estribillistas were: Ernesto Famá, Charlo, Teófilo Ibañez, Francisco Fiorentino, Roberto Ray, Carlos Dante, Agustín Irusta, Jorge Omar.

|

Table 1: Hearing the difference between an "estribillista" and a "cantor nacional"

Listen to these two versions of the same exact song:

"Casas Viejas" by Francisco Canaro with Roberto Maida

"Casas Viejas" by Francisco Canaro with Charlo y Ada Falcon

Would it surprise you to learn that both versions were recorded only a week apart? The Roberto Maida version was recorded on 8/16/1935 and the Charlo/Falcon version on 8/25/1935. Hmmmm... So why would Canaro do that?

Because there were two different audiences for tango music, the general public and dancers.

In the first version, Maida is acting as an "estribillista." He is at the service of the orchestra. He only sings for a short time and blends with the orchestra. Also, notice the strong walking beat (pulse) in the music. This version is for dancers. Now technically, he is not singing the chorus/refrain, he is singing the first verse of the song, but it is still just the first verse. He is not singing the full lyrics of the song (verse, chorus, verse), he is just singing 1/3 of the lyrics and does not even start singing until 1:39 into the song.

In the second version, Charlo and Ada Falcon are soloists or cantor nacional. The entire lyric gets sung, the first verse by Charlo and then Falcon joins in to make it a duet for the chorus and the final verse. The walking beat is not as clear and is in the background, the orchestra is in service of the singers. Sometimes the beat even completely disappears, this would be very difficult for dancers. This is not for dancing. |

The Orchestra Singer (Cantor de la Orchesta)

In the mid-1930s and early 1940s, the role of the singer was evolving. The singer was becoming a more and more important member of the orchestra. People would come to shows or buy records to hear a particular singer. Orchestras and singers became more linked, for instance one might say Di Sarli y Rufino, Di Sarli y Podesta or Troilo y Fiorentino.

So what is the difference between an “estribillista” and a “cantor de la orchesta?” It is a combination of the emphasis put on the lyric and the length of time of the singing. For instance, an “estribillista” would only get a single chorus or a single verse to sing (approx 30 seconds), but the “cantor de la orchesta” would get to sing a verse, a chorus and often a repeat of the chorus at the very end (60 seconds or more). It is important to note that they were still a member of the orchestra and rarely got to sing the whole lyric. As with the "estribillista," they were still very much in service to the orchestra.

Generally, a typical tango goes verse, chorus, verse, chorus, verse, outro (coda). The “cantor de la orchesta” will generally enter the song on the 2nd verse or about 1 minute into the song. This is important for dancers! We get to hear one full verse and chorus without singing, so that we can feel the music and already be familiar with the accents of the music before the singer begins.

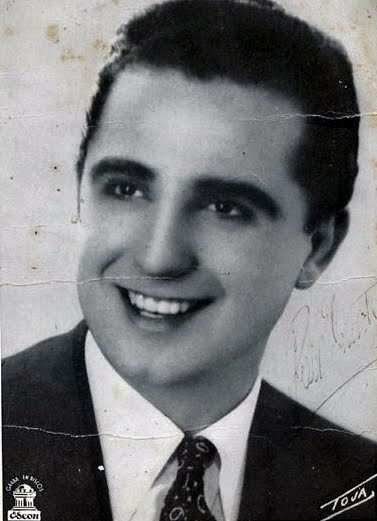

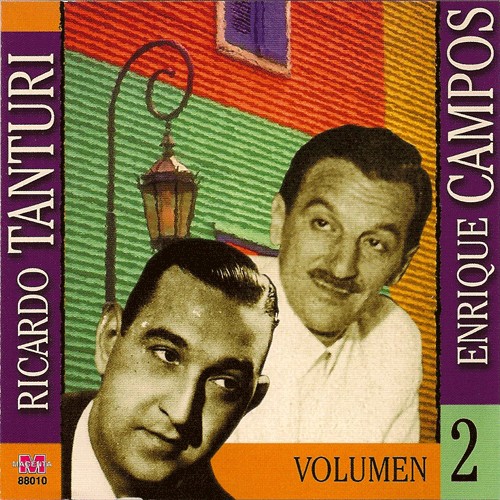

You can hear the transition from “estribillistas” into “cantors de la orchesta” beginning in the mid-1930s in Jorge Ortiz with Lomuto, Roberto Ray with Fresedo, Horacio Lagos with Donato and Roberto Maida with Francisco Canaro. But when we speak of “cantor de la orchesta,” some of the singers that we think of are Francisco Fiorentino and Alberto Marino with Troilo, Ángel Vargas with D’Agostino, Alberto Castillo and Enrique Campos with Tanturi, Raúl Berón with Caló, Roberto Rufino and Alberto Podesta with Di Sarli, Alberto Echagüe and Héctor Mauré with D’Arienzo.

After 1941, you can’t find many instrumentals, because of the popularity of the singers. It also marked a change in tango music to a more smooth, melodic sound.

Here are two good examples of the "cantor de la orchesta:"

"Tinta Roja" by Aníbal Troilo with Francisco Fiorentino

"Nada" by Carlos Di Sarli with Alberto Podesta

"Al Compas del Corazón" by Miguel Caló with Raúl Berón

"Tres Esquinas" by Ángel D'Agostino with Ángel Vargas

"Palomita Blanca" (1944) by Aníbal Troilo with Floreal Ruiz and Alberto Marino

This is the same song as above. In the above version, the singer sang all of the lyric and sang pretty much throughout the song. In this version, the singing does not begin until the 2 minute mark and the singers sing 1 verse and 1 chorus.

|

Table 2: Same Singer, Two Different Roles

As mentioned above, many singers transitioned from the role of the "estribillista" to that of a "cantor de la orchesta." Alberto Echagüe was one of these. Listen to the two tangos below. In "Pénsalo Bién," Echagüe is a classic example of an "estribillista." He only briefly sings the chorus. Just a year later, in "Trago Amargo," he is singing the first verse, the chorus, and a touch of the final verse. His role as expanded.

"Pénsalo Bién" by Juan d'Arienzo with Alberto Echagüe (1938)

"Trago Amargo" by Juan d'Arienzo with Alberto Echagüe (1939)

|

The Star Soloist

There is a reason that the vast majority of the music played at milongas is from the “golden decade (1935 to 1945)” and not from the “golden age (1935 to 1955)” of tango. In the mid-1940s, the singers began to become more important than the orchestras. In fact, many of the most popular singers left to start their own orchestras such as Alberto Castillo, Francisco Fiorentino and Ángel Vargas.

The distinguishing features of the soloist is that they are the star and the orchestra is more in the background and they sing the entire lyric of the song. This phenomenon became more pronounced as the youth of Argentina began to dance other dances and most tango music was more for listening. Some famous star soloists were Edmundo Rivero, Roberto Goyeneche, Alberto Morán, Miguel Montero, Jorge Vidal and Argentino Ledesma.

It should be noted that some orchestras, such as Di Sarli, kept a focus on the dancer while giving the singer more prestige.

"Tinta Roja" by Aníbal Troilo with Roberto Goyeneche

Notice the difference between this version and the version above. It is the same orchestra, but from a different time and with a different focus on the singer.

"Duelo Criollo" by Alberto Marino

"Sur" by Edmundo Rivero

Conclusion

For DJs and dancers, most of the music that we dance to has singers, but we primarily dance to singers when they are acting as an “estribillista” or “cantor de la orchesta.” Most of this music was recorded between 1935 and 1945, but there are exceptions.The main thing to listen for is if the singer sounds like he/she is above the orchestra, if the singer is much louder and you can not clearly hear the music then it is not good for dancing. Always keep in mind that the vast majority of tango music was not intended for dancers. Tango is about much more than dancing, it is also poetry, music, culture, art, etc.

Disclaimer: Yes. You might can find examples that don't fit these conclusions or time spans. What I am trying to look at here is what was the norm.

Sources

Here is a list of some of the sources that I used to put this article together:

Todo Tango's Article: The Tango Singer