This week's traditional tanda is a set by Angel D'Agostino with Angel Vargas singing.

Last week, we looked at a milonga set by D'Agostino - Vargas, so this week we are looking at a tango set.

| Home > Tango Resources > Tangology 101 Blog |

This week's traditional tanda is a set by Angel D'Agostino with Angel Vargas singing.

Last week, we looked at a milonga set by D'Agostino - Vargas, so this week we are looking at a tango set.

This week's traditional tanda is a milonga set by Angel D'Agostino with Angel Vargas singing.

I love all of these milngas, but "El Porteñito" is one of my all time favorites.It was originally written in 1903 by Angel Villoldo.

In Part I of this article, we looked at the basic structure of tango which consists of 5 distinct parts: A (verse) -- B (chorus) -- A (verse) -- B (chorus) -- A (versue. It was mentioned that not all tangos, fit neatly into this structure, but that this simple structure is usually present.

Caminito

Let's start with an older tango "Caminito" performed by Francisco Canaro from 1926. This song has several variations to the basic structure, but as you will see, that basic structure is still there. This song structure goes:

intro -- verse -- pre-chorus -- chorus -- verse -- pre-chorus -- chorus -- verse

Caminito (The Whole Song)

Caminito (Introduction)

Caminito (Verse 1)

Caminito (Pre-Chorus and Chorus 1)

Caminito (Verse 2)

Caminito (Pre-Chorus and Chorus 2)

Caminito (Verse 3)

Introduction

"Caminito" has a cute little 8 second introduction, before the first verse begins. This is very common and happens often in tangos. Dancer's Note: This introduction actually does have a strong beat, but usually they will not, so we rarely dance to an introduction. In fact, we usually don't start dancing until the first beat of the second phrase of a typical tango song, so if the song has an introduction, we might begin dancing on the first beat of the first verse.

Pre-Chorus

After before each chorus in "Caminito," there is a pre-chorus that lasts for about 8 seconds which consists of a bandoneón solo and then a piano solo. Sometimes you can also have pre-versus which work the same way, but before the each verse. Dancer's note: This is a good time to execute a corté (break) or parada (stop) and for women to embellish. It might also be a good time for a calesita. Basically, something which keeps us from progressing.

Humming and Whistling

One other interesting note about this song, is that during the first chorus you can hear the band members humming or moaning the chorus and during the second chorus someone is whistling the chorus. This song was recorded in 1926 and singers were not added to dance orchestras until 1927, when Canaro recorded "Así es el Mundo," featuring Roberto Díaz, as a chorus singer. See my article on "The Role of the Orchestra Singer" for more information on this subject.

Poema

"Poema" is a very popular tango which was recorded in 1935 by Francisco Canaro with Roberto Maida singing. It has a very distinct variation on the basic structure, while still keeping the verse -- chorus -- verse -- chorus -- verse structure. Listen to the song and then see if you can hear what it is.

Poema (The Whole Song)

Poema (Verse 1)

Poema (Chorus 1)

Poema (Verse 2)

Poema (Chorus 2)

Poema (Verse 3)

The first verse is 32 single-time beats, as we would expect, but then the chorus is only 16. Then the second verse is a whole 64, instead of the usual 32. Then the chorus is only 16 again and the final verse is 64.

Also, listen to verse 1 and then verse 2, there is no better example of a singer performing as an instrument of the orchestra. In the 2nd verse, notice that Maida imitates the violin of the 1st verse. The singer and the violin accent almost the same notes.

Dancer's note: "Poema" is also a great example of the choruses being more rhythmic than the verses. The tempo is the same, but notice how the energy goes up. There is actually a strong beat during the verses, but the melodic rhythm is equal if not dominant. During the verses, you have an option to dance to the beat or to the melody or switch between phrases. There is less option during the chorus, there is little melody and the beat is very dominant. Below is a performance of "Poema" by Murat and Michelle Erdemsel. It includes a painting of his which visually represents the different sections of "Poema." You will see the melodic sections represented as blue circles and the more ryhtmic sections represented by a rectangle with sharper lines and deeper colors.

Below are two great performances to "Poema" by Pablo Rodriguez and Noelia Hurtado and Javier Rodriguez and Geraldine Rojas. See you can see how they shift in energy between the choruses and verses. Also, notice that they both begin with a step on the fist beat of the 2nd phrase, this is not at all necessary, but is very common.

Rhythm vs Melody

The rhythm of a song is the basic beat, "pulse," or steady flow of the music. The rhythm is what you would clap your hands to or change weight to as you listen to a piece of music.

The melody or melodic rhythm is the "wave" of the music or what you would hum. Melody would consist of the shape, movement and intensity of the notes to one another.

Usually, the rythm is played by the accompaniment consisting of piano, double base and one bandoneon while the rest of the instruments play the melody or solos. You might have two melodies playing at the same time, overlapping each other, such as two bandoneons playing different melodies. Also, melodies will often repeat, with variations, throughout the song.

The rhythm would be each individual sound, while the melody is the wave-form of those sounds. If you just listen to a single measure, you will not hear the melody. If you listen to a phrase then you will hear the melody. The melody might last from anywhere from one phrase (see below) to a whole section of the song. Melody is not just about the notes played, but HOW they are played and where the accents are placed.

Dancer's Note: Imagine the rhythm as being a steady base that lies underneath with the melody floating on top.

As dancers, we want to be aware of both the rhythm and the melody. We can dance to either one, but the mark of an advanced dancer is being able to hear which is dominant and be able to adapt their dance accordingly. If both are equal, then it is up to the leader.

Also, you want to hear the flow of the melody, so that you can hear the melodic accents and climaxes in the music. These accents will often correspond to a beat of the rhythm. If we are dancing to the melody, this when we want to step or perform a boleo or gancho. The accents can be placed on any beat, but almost always on the first beat of a measure. You don't necessarily have to "know" the song by heart to hear these accents coming. Since tangos often repeat themselves, if we pay attention to the first verse and to the first chorus then we should have a good idea of where the accents are going to be for the rest of the song. I say a good idea, because often accents do change from section to section.

Measures

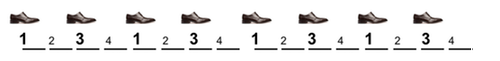

Tango music is in 4/4 time (4 beats per measure), two upbeats and two downbeats (strong). In the graphic below, 1 is a downbeat, 2 is an upbeat, 3 is a downbeat and 4 is an upbeat. Dancer's Note: As tango dancer's we first learn to step in "single-time," which means to walk on the downbeats, so we step on the 1 and the 3. Then we learn double-time, half-time and syncopation. To dance just in single-time would be very boring. We will look at these other times the article Musicality 101.

One measure in 4/4 time:

Phrases

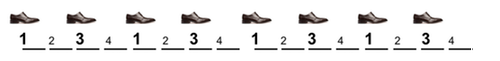

Each of the 5 sections of a tango are made up of 4 phrases. A phrase consists of 4 measures or 8 single-time beats, so each section has 32 sing-time beats.

One phrase in 4/4 time:

One Section (Four Phrases):

Exercise: Let's listen to "Que Nunca Me Falte" by Ricardo Tanturi. In this song, you can clearly hear the ending of each phrase. You will notice that each phrase ends on the seventh walking (strong) beat and that the eight is silent. Then the next phrase begins with a strong 1.

Deeper into Phrases

The understanding of phrasing is one of the most important aspects to good musicality. I like to think of a tango as a story, each section as a paragraph, each phrase as a sentence and each beat as a word. While words (beats) do convey meaning, the sentence (phrase) is really the most important thing to express.

These sentences can convey a simple statement, exclaim strong emotion or can even ask a question. My favorite way of thinking of a section of tango music is that there is a question and then an answer (call and response). This can take many forms. The first phrase might be a question which then gets answered by phrase 2.

Let's listen to the first two phrases of "Bahía Blanca:"

Phrase 1 & 2 of "Bahía Blanca:"

Phrase 3 & 4 of "Bahía Blanca:"

I like to think that the first two phrases are a statement or question and that the last two phrases are a sharp response. You can even hear Di Sarli putting a period or exclamation mark at the end of the last phrase with the piano "ping." The last phrase of a section usually ends more dramatically with some sort of strong punctuation to let you know that the section is over and that a new section is beginning.

Dancer's Note: In my opinion, being able to hear the ebb and flow of the phrases and the resolution of phrases is one of the most important concepts to understand about the music. Notice if the phrases are flowing together or if each phrase is ending in a strong period or comma (pause) and exploit that knowledge in your dance. It is especially important to be able to hear the end of the final phrase of any section, as those mark crucial transitions within the song.

The end of sections, is where we want to pause or end an idea such as a turn or sequence. It is SUPER important not to "blur" the end of a section, if there is a pause in the music. Imagine that at the end of a section is a red light, which you need to acknowledge. The first beat of the next section is your "green light" to move again.

The Outro or Coda (tail)

The outro is usually the final verse of the song. It is usually very similar to the first two verses, but will often include an instrumental solo or some slightly different instrumentation. Often the outro will gain in energy leading up to the final chum-chum. Listen to the Outro (Verse 3) of "Pensalo Bien" and notice the bandoneón solo runs.

"Pensalo Bien" Verse 3

Chum-Chum

The final two notes of a tango are often referred to as chum-chum. Many orchestras put their own unique stamp on the chum-chum.

End of "Al Compas del Corazon" by Miguel Caló

Strong first chum -- pause -- soft piano notes for second chum

End of "Llorar Por Una Mujer" by Enrique Rodriguez

Rodriguez probably has the most famous ends, because he would only do the first chum and then skip the second chum.

End of "La Yumba" by Osvaldo Pugliese

Strong first chum -- pause -- Soft second chum

End of "La Vide Es Corta" by Ricardo Tanturi

Strong first chum -- pause -- piano note for second chum

In this article we will learn about the basic structure of Argentine Tango. In very simple terms, most tangos consist of the following elements:

The Basic Structure

The basic structure of a simple Argentine Tango consists of 5 sections. Some people like to describe this structure as ABAB and others say that it is ABABC, meaning that often the last section often has a little different structure than the previous A sections. Often, in this final section there will be some sort of instrumental solo. But there is nothing guaranteed. Sometimes sections are longer or shorter or have little intros to the sections. This is just a general structure to listen for and the really important thing for dancers is to hear wihen these sections are coming to an end and when a new one begins.

A Sections (or Verses)

I like to think of the A sections as verses. In popular music, this would correspond to the lyric of the song and a singer would sing all three verses. In tango, the first verse is almost always an instrumental. The second verse, is either an instrumental or sung depending on the orchestras use of a singer. The third verse, is often an instrumental with a solo, but it is occasionally sung.

In tango, the verses are usually musically similar. So, if you pay attention to the first verse, it is likely that the next verses will follow a similar pattern. Also, verses are usually more melodic in nature.

B Sections (or Chorus / Refrain)

The B section is usually repeated twice and will be the same both musically and lyrically. Once again, the first chorus is not sung in most tangos, for dancing. If the song is not an instrumental, the second chorus is almost always sung, but of course there are variations. The chorus usually has a more upbeat and more rhythmic feel than verse, but not always.

Dancer's Note: This structure helps us as dancers, if we pay attention to the first verse and the first chorus, then we will know, within reason, what to expect for the rest of the song.

Exercise: Let's listen to Carlos Di Sarli's "El Jagüel" from 1956. If you listen closely, you will clearly hear the end of each section. Di Sarli ends each section with a single ping of the piano. If you listen a few times, you will hear the music build up to the end of each section.

Now let's listen to two famous tangos, "Bahía Blanca" by Carlos Di Sarli from 1957 and "Pensalo Bien" by Juan D'Arienzo with Alberto Echagüe singing from 1938, and see if we can hear this structure.

Bahía Blanca

"Bahía Blanca" is an homage to Carlos Di Sarli's hometown, which is located in the south-west province of Buenos Aires. It is a great example of an elegant, sophisticated tango.

"Bahía Blanca" is an homage to Carlos Di Sarli's hometown, which is located in the south-west province of Buenos Aires. It is a great example of an elegant, sophisticated tango.

First, let's listen to the whole song:

Bahía Blanca (The Whole Song)

Next, let's listen to the 5 sections independently of each other.

Bahía Blanca (A 1)

Bahía Blanca (B 1)

Bahia Blanca: B 1

Bahía Blanca (A 2)

Bahía Blanca (B 2)

Bahía Blanca (A 3)

Now, go back and listen to A 1, A 2 and A 3 and notice the similarity. You will notice small differences in the instrumentation, but the overall structure is very similar. Then go back and listen to B 1 and B 2. You should find them very similar as well.

Pensalo Bien

Now let's examine "Pensalo Bien" in the same fashion. First, let's listen to the whole song:

Now let's examine "Pensalo Bien" in the same fashion. First, let's listen to the whole song:

Pensalo Bien (The Whole Song)

Next, let's listen to the 5 sections independently of each other:

Pensalo Bien (A 1)

Pensalo Bien: Verse 1

Pensalo Bien (B 1)

Pensalo Bien: Chorus 1

Pensalo Bien (A 2)

Pensalo Bien: A 2

Pensalo Bien (B 2)

Pensalo Bien: B 2

Pensalo Bien (A 3)

Pensalo Bien: A 3

The first difference that we might notice is small, but each verse begins with a slight 2 second intro played only by the bandoneon. Another noticeable difference here is that Alberto Echagüe sings the second chorus. Echagüe is playing the common role of the tango singer as an "estribillista" or chorus singer.

In the vast majority of tango songs, played for dancing, the singer will only sing a small portion of the lyric. Usually they will only begin singing during the second verse and/or the second chorus. This helps us as dancer's, because we get to hear a whole verse and chorus without singing, so that we can hear the musical structure before the singing starts. For more on the singer's role in the tango orchestra read my article: The Role of the Tango Orchestra Singer.

Tempo

One difference to notice between these two songs is the tempo. Tempo is the overall pace (beats per minute) of a piece of music. Both songs have the same amount of beats, but "Bahía Blanca" is 2:52 while "Pensalo Bien" is 2:18. What is different is the beats per minute. "Bahía Blanca" is played at approximately 56 bpm and "Pensalo Bien" is played at approximately 67 bpm. When I say beat, I am referring to the "walking beat" (aka downbeat or strong beat), which I will explain more in a moment.

Dancer's Notes: Tempo has a lot to do with our style of dancing. Below are some examples of how we might modify our dance depending on tempo. Notice that I keep using the word "might" as these are general ideas and not absolutes. We might do exactly the same steps in both, but the quality that we give to those steps might be very different.

| Faster Tempo | Slower Tempo |

|---|---|

| We might dance in a closer embrace. The embrace might be slightly firmer so that we stay connected while moving faster. BUT should not be too firm where the woman might not be free to move. | We might feel like opening the embrace periodically for more challenging steps. The embrace might be less firm, giving her plenty of room to pivot and take larger steps. |

| We might walk more staccato, meaning that we might walk with shorter steps and we might begin and/or end our steps more sharply. | We might walk more legato, meaning that we might feel like taking larger, longer steps and to walk more smoothly through our steps. |

| We might be more playful with our steps and embrace. | We might be more serious and dramatic. |

| We might move more linearly. | We might curve our steps and movements more. We might allow for more fluidity in our embrace. We might do more turning walks and more turns in general. |

| We might maintain a more constant flow and pause less or we might pause quickly and then begin again quickly. | We might use long dramatic pauses and then begin moving again very slowly. |

| We might try to step on most every beat, rarely skipping beats. | We might skip beats and really stretch out our steps. |

| We might work in quick embellishments with little flurries of their feet or quick toe taps. | We might work in more long, stretched out embellishments, which the men should wait and give the women time to complete. |

| We might use more rebound steps with lots of quick changes of direction. | |

| We might use the quick, quick, slow rhythm more. We also might use the quick, quick, quick, quick, slow rhythm. | We will always dance with rhythm, but that rhythm might be more sub-dued and a the "slow" of the quick, quick, slow might be stretched out a bit more. |

My goal here is to provide a well-rounded explanation of the structure of Argentine Tango music, with a focus on the dancer. I am dealing here with tango music that is meant for dancing, starting in the mid-1920s. This is the music that you will hear at the milongas. This does not cover early tango music, tango cancion or the more modern music of Piazzolla.

The first part of this article deals with the basic structure and a discussion of tempo. The second deals with measures and phrasing and the relationship between melody and rhythm. The third part deals with more complex variations on the basic structure. In the future, there will be articles on musicality and additional subjects on Argentine Tango music.

Why is understanding this structure important for dancers? When we dance we have a connection with our partner, the other couples on the dance floor and with the music. This connection to the music is what we will explore in these articles. Most dancer's musicality ends with being able to pause and throwing in a quick-quick-slow here and there. Understanding the structure allows us to better predict when the changes in rhythm will occur, thus when to use those pauses and rhythm changes.

Site Link: http://www.milonga.me/

Join other Tango lovers and milongueras, don't miss any festivals and discover who is in - worldwide and mobile! Whether beginner or tanguero: You are welcome!

This week's traditional tanda is a elegant and romantic set by Miguel Caló with Raúl Iriarte singing.

Caló had created a unique sound around Berón's smooth vocal style, which was unlike the other singers of the time. In 1943, Berón left Caló's orchestra to join Demare's orchestra. Caló briefly worked with Jorge Ortiz and Alberto Podesta during 1943, but ended up with Raúl Iriarte, who had a similarly silky vocal quality to Berón.

I often get asked about dancing to tangos with singers. The tango singer has had four distinctive roles over time:

These roles are not tied to specific dates, and they often overlapped in time.

Why is this important for dancers and DJs? The role of the singer impacts the structure of the music. Understanding this structure can help us as dancers. For DJs, we should understand which tangos are meant for and are good for dancing. The tangos best for dancing are the ones which utilize the singer as estribillista or as cantor de la orchesta. I will explain why.

The National Singer (Cantor Nacional)

From the earliest days of tangos, singers would accompany guitarists (sometimes pianos) or “typical trios.” They would sing all the lyrics of a song including verses and choruses (refrain). These duos or groups would usually play tangos, valses, and milongas, along with folk songs such as zambas, rancheras, tonadas. These singers were called “cantor nacional,” and they would be able to sing in all of these styles. Below is an example of a typical tango duo Corsini y Magaldi with Ignacio Corsini singing and Agustin Magaldi on guitar. Notice that Corsini sings the full lyrics: verse, chorus, verse, chorus.

"Palomita Blanca" by Ignacio Corsini (singer) & Agustin Magaldi (guitar)

This type of singer would also be employed for the tango canción. These were songs that were not intended for dancing and were mostly sentimental in nature. The most famous tango canción was probably "Mi Noche Triste (My Sad Night)" recorded in 1917 by Carlos Gardel.

"Mi Noche Triste" by Carlos Gardel (1917)

Some of the famous "cantors nacional" were Carlos Gardel, Ignacio Corsini, Hugo del Carril, Charlo, Agustín Magaldi, Alberto Gómez and Agustín Irusta.

The Refrain Singer (Estribillista)

When the orquesta típica was created in the early 1900s, they primarily played instrumentals. Sometimes a member of the orchestra might say something, but it was usually for humorous effect rather than singing. In his memoirs, Francisco Canaro claims that he was the first to use an estribillista in his orchestra. In 1927, he recorded his brother’s tango “Así es el Mundo,” which featured Roberto Díaz. Unfortunately, I have not yet been able to find a copy of this song.

So what defines an estribillista? An estribillista was restricted to singing a very small portion of the lyrics, usually the chorus (refrain) or just a single verse. They were considered just another instrument and were often not even mentioned on the record label and if they were then it was in very small type. Sometimes they were employed by a specific orchestra, but often they were employed by the recording label and would sing for all the orchestras under that label.

Some important estribillistas were: Ernesto Famá, Charlo, Teófilo Ibañez, Francisco Fiorentino, Roberto Ray, Carlos Dante, Agustín Irusta, Jorge Omar.

|

Table 1: Hearing the difference between an "estribillista" and a "cantor nacional" Listen to these two versions of the same exact song: "Casas Viejas" by Francisco Canaro with Roberto Maida

"Casas Viejas" by Francisco Canaro with Charlo y Ada Falcon Would it surprise you to learn that both versions were recorded only a week apart? The Roberto Maida version was recorded on 8/16/1935 and the Charlo/Falcon version on 8/25/1935. Hmmmm... So why would Canaro do that? Because there were two different audiences for tango music, the general public and dancers. In the first version, Maida is acting as an "estribillista." He is at the service of the orchestra. He only sings for a short time and blends with the orchestra. Also, notice the strong walking beat (pulse) in the music. This version is for dancers. Now technically, he is not singing the chorus/refrain, he is singing the first verse of the song, but it is still just the first verse. He is not singing the full lyrics of the song (verse, chorus, verse), he is just singing 1/3 of the lyrics and does not even start singing until 1:39 into the song. In the second version, Charlo and Ada Falcon are soloists or cantor nacional. The entire lyric gets sung, the first verse by Charlo and then Falcon joins in to make it a duet for the chorus and the final verse. The walking beat is not as clear and is in the background, the orchestra is in service of the singers. Sometimes the beat even completely disappears, this would be very difficult for dancers. This is not for dancing. |

The Orchestra Singer (Cantor de la Orchesta)

In the mid-1930s and early 1940s, the role of the singer was evolving. The singer was becoming a more and more important member of the orchestra. People would come to shows or buy records to hear a particular singer. Orchestras and singers became more linked, for instance one might say Di Sarli y Rufino, Di Sarli y Podesta or Troilo y Fiorentino.

So what is the difference between an “estribillista” and a “cantor de la orchesta?” It is a combination of the emphasis put on the lyric and the length of time of the singing. For instance, an “estribillista” would only get a single chorus or a single verse to sing (approx 30 seconds), but the “cantor de la orchesta” would get to sing a verse, a chorus and often a repeat of the chorus at the very end (60 seconds or more). It is important to note that they were still a member of the orchestra and rarely got to sing the whole lyric. As with the "estribillista," they were still very much in service to the orchestra.

Generally, a typical tango goes verse, chorus, verse, chorus, verse, outro (coda). The “cantor de la orchesta” will generally enter the song on the 2nd verse or about 1 minute into the song. This is important for dancers! We get to hear one full verse and chorus without singing, so that we can feel the music and already be familiar with the accents of the music before the singer begins.

You can hear the transition from “estribillistas” into “cantors de la orchesta” beginning in the mid-1930s in Jorge Ortiz with Lomuto, Roberto Ray with Fresedo, Horacio Lagos with Donato and Roberto Maida with Francisco Canaro. But when we speak of “cantor de la orchesta,” some of the singers that we think of are Francisco Fiorentino and Alberto Marino with Troilo, Ángel Vargas with D’Agostino, Alberto Castillo and Enrique Campos with Tanturi, Raúl Berón with Caló, Roberto Rufino and Alberto Podesta with Di Sarli, Alberto Echagüe and Héctor Mauré with D’Arienzo.

After 1941, you can’t find many instrumentals, because of the popularity of the singers. It also marked a change in tango music to a more smooth, melodic sound.

Here are two good examples of the "cantor de la orchesta:"

"Tinta Roja" by Aníbal Troilo with Francisco Fiorentino

"Nada" by Carlos Di Sarli with Alberto Podesta

"Al Compas del Corazón" by Miguel Caló with Raúl Berón

"Tres Esquinas" by Ángel D'Agostino with Ángel Vargas

"Palomita Blanca" (1944) by Aníbal Troilo with Floreal Ruiz and Alberto Marino

This is the same song as above. In the above version, the singer sang all of the lyric and sang pretty much throughout the song. In this version, the singing does not begin until the 2 minute mark and the singers sing 1 verse and 1 chorus.

|

Table 2: Same Singer, Two Different Roles As mentioned above, many singers transitioned from the role of the "estribillista" to that of a "cantor de la orchesta." Alberto Echagüe was one of these. Listen to the two tangos below. In "Pénsalo Bién," Echagüe is a classic example of an "estribillista." He only briefly sings the chorus. Just a year later, in "Trago Amargo," he is singing the first verse, the chorus, and a touch of the final verse. His role as expanded. "Pénsalo Bién" by Juan d'Arienzo with Alberto Echagüe (1938)

"Trago Amargo" by Juan d'Arienzo with Alberto Echagüe (1939)

|

The Star Soloist

There is a reason that the vast majority of the music played at milongas is from the “golden decade (1935 to 1945)” and not from the “golden age (1935 to 1955)” of tango. In the mid-1940s, the singers began to become more important than the orchestras. In fact, many of the most popular singers left to start their own orchestras such as Alberto Castillo, Francisco Fiorentino and Ángel Vargas.

The distinguishing features of the soloist is that they are the star and the orchestra is more in the background and they sing the entire lyric of the song. This phenomenon became more pronounced as the youth of Argentina began to dance other dances and most tango music was more for listening. Some famous star soloists were Edmundo Rivero, Roberto Goyeneche, Alberto Morán, Miguel Montero, Jorge Vidal and Argentino Ledesma.

It should be noted that some orchestras, such as Di Sarli, kept a focus on the dancer while giving the singer more prestige.

"Tinta Roja" by Aníbal Troilo with Roberto Goyeneche

Notice the difference between this version and the version above. It is the same orchestra, but from a different time and with a different focus on the singer.

"Duelo Criollo" by Alberto Marino

"Sur" by Edmundo Rivero

Conclusion

For DJs and dancers, most of the music that we dance to has singers, but we primarily dance to singers when they are acting as an “estribillista” or “cantor de la orchesta.” Most of this music was recorded between 1935 and 1945, but there are exceptions.The main thing to listen for is if the singer sounds like he/she is above the orchestra, if the singer is much louder and you can not clearly hear the music then it is not good for dancing. Always keep in mind that the vast majority of tango music was not intended for dancers. Tango is about much more than dancing, it is also poetry, music, culture, art, etc.

Disclaimer: Yes. You might can find examples that don't fit these conclusions or time spans. What I am trying to look at here is what was the norm.

Sources

Here is a list of some of the sources that I used to put this article together:

Todo Tango's Article: The Tango Singer

This week's traditional tanda is wonderful set by Juan d'Arienzo with Héctor Mauré.

The role of the tango singer was evolving in 1940, when Mauré joined D'Arienzo's orchestra. The singer was taking a stronger role and combinations such as Di Sarli/Rufino and Troilo/Fiorentino were having a lot of success. Mauré's smooth, lyrical style might not have seemed like a good fit for D'Arienzo's more rhythmic orchestra, but it worked. Between 1940 and 1944 D'Arienzo and Mauré recorded about 50 tracks.