The second part of the Guardia Vieja period lasted from approximately 1910 to 1935. I say approximately because the styles and changes of this period blended very smoothly with the preceding and following periods. It is not as if on January 1, 1910 people started composing and playing differently.

This period saw:

- Tangomania sweep Europe and the US

- Greater acceptance by the middle and upper classes of Buenos Aires

- The formation of the Orquesta Tîpica

- Carnivals

- Tango-canción take off with Carlos Gardel

- The advent of the women's orquestas.

Tangomania

Up until the early 1910s, tango had largely been a past time of the lower classes. It had been played and danced in cafés, bordellos, restaurants, conventillos but not in the salons of the elite. After Tangomania swept Europe and the US, this all changed and tango began to be embraced by the middle and upper classes of Buenos Aires. It is impossible to understate the popularity of Tango in Europe. It was the rage of the salons and made headlines in newspapers.

Enrique Saborido, the composer of many tangos including "La Morocha," also travelled to Europe to teach people how to properly play tango and ended up also teaching people to dance:

"The marquise Reské, widow of the famous tenor Jean Reské, was willing to popularize Argentine tango among the French. It was around 1911 and I accepted such formal invitation; when in Paris, at the beginning I devoted to teaching tango playing, so that it would be correctly performed. As I had spare time and I had noticed that the high society people were really interested in it, I taught them how to dance it.

One night at the marquise palace where a reception was held I organized, with the approval of the attendance, a pericón (traditional Argentine dance) whose steps proved to be very attractive for everybody and were warmly applauded.

On another occasion I was appointed referee to demonstrate that the forlana was not more decent than tango; the dissent was even reflected in the chronicles at the papers and the Catholic paper "Le Gaulois" finally regarded tango as a beautiful graceful dance.

Thereafter the outbreak of war forced me to come back to Buenos Aires."

Acceptance

It is also impossible to understate the influence that Europe's acceptance, particularly France's, had on Buenos Aires. It is joked that, porteños were Italians that spoke Spanish, thought they were British and wished they were French. Anyone who visits Buenos Aires cannot deny the influence of French architecture.

Orquesta Tîpicas

Orquesta Tîpicas

In 1911, Vincente Greco was asked to record some tangos by Columbia and he created the first Orquesta Típica Criolla. Over time the "criolla" was dropped from the name. The original Orquesta Tîpicas were sextets which consisted of two bandoneons, two violins, a double bass and a piano (sometimes a guitar or flute were substituted). Eventually they grew to include a string section (with violins, viola, and cello), a bandoneón section (with 3 or more bandoneons), and a rhythmic section (with piano and double bass). The piano was first added by Roberto Firpo in 1913 and the double bass by Francisco Canaro in 1917.

Around 1916, Firpo re-wrote a march by Gerardo Mattos Rodriguez as a tango. It would become the most famous of all tangos, "La Cumparsita."

Carnivals

Carnivals were huge events where massive amounts of people would come to hear the most popular orquestas of the day. Orquestas would save their best new pieces to debut them at the carnivals. Carnivals were very popular with dancers. Many dance academias would advertise to dancers, "Come and learn the best new figures for the carnival."

Tango Canción

Up to this point, tango lyrics had been dark, but humorous. In 1917, Carlos Gardel recorded Pascual Contursi's "Mi Noche Triste." Now Contursi could have meant the lyrics to be ironic but Gardel sang the song with melodramatic longing and sadness. This song struck a cord with the newly arrived immigrants, who were missing their countries, families and wives and was hugely successful, launching a new genre "tango-canción." Tango-canción was full of drama, sentimentality, sadness and nostalgia.

In 1920, the first tango written as a song, "Milonguita." Up until that time, tangos had been written as music first and then lyrics added later. This was the first time that a song was written as lyrics first. It was turned into a movie in 1922 and was the first to feature the theme of the poor, country girl who leaves home to go to the big city of Buenos Aires and becomes a prostitute.

In 1920, the first tango written as a song, "Milonguita." Up until that time, tangos had been written as music first and then lyrics added later. This was the first time that a song was written as lyrics first. It was turned into a movie in 1922 and was the first to feature the theme of the poor, country girl who leaves home to go to the big city of Buenos Aires and becomes a prostitute.

Women's Orquestas

Paquita Bernardo was the first professional female bandoneon player and Carlos Gardel said she was, "the only woman who has mastered the macho character of the bandoneon." The debuted her sextet in 1921. There were many women's orquestas and they were popular between 1920 and into the early 1930s. They often played in confiterías, cafés, bars, for weddings and parties. To the best of my knowledge, no women's Orquesta was ever recorded, but there is some film footage of one from the 1933 film, "Tango!"

Paquita Bernardo was the first professional female bandoneon player and Carlos Gardel said she was, "the only woman who has mastered the macho character of the bandoneon." The debuted her sextet in 1921. There were many women's orquestas and they were popular between 1920 and into the early 1930s. They often played in confiterías, cafés, bars, for weddings and parties. To the best of my knowledge, no women's Orquesta was ever recorded, but there is some film footage of one from the 1933 film, "Tango!"

“Cara Sucia” (1917)

“Cara Sucia” (1917)

Composer: Francisco Canaro y 'El Negro' Casimiro Alcorta

Performed by: Francisco Canaro

Some song titles and lyrics were changed because the originals were so vulgar. "Concha Sucia" was a traditional song believed to have been composed by 'El Negro' Casimiro Alcorta, a black violin player from the earliest days of tango. The title literally translates to "Dirty Shell," but concha (shell) was a common, obscene term for vagina. Canaro registered this tango, under his own name, and changed the song title to "Cara Sucia" in 1916. Canaro is believed to have done this with several of the old tangos. The name change was probably to conform to the changing audience of tango, which was including more women and the middle class.

More on Francisco Canaro: http://www.todotango.com/...

Songs of this Period

Rosendo by Orquesta Tipica Criolla (1912)

Don Juan by Alfredo Gobbi

Miniquito by Flora Gobbi (1911)

La Montura by Genaro Exposito (1912)

Armenonville by Juan Pacho Maglio (1912)

Venus by Juan Pacho Maglio (1912)

El Estribo by Vicente Greco (1912)

El Apache Argentino by Arturo A. Mathon (1913)

El Choclo by Orquesta Tipica Portena (1913)

Mi Preferido by Orquesta Criolla Domingo Biggeri (1913)

Region Campera by Quinteto Criollo El Aleman (1913)

Pura Uva by Quinteto Garrote (1913)

Recuerdos de Zambonini by Quinteto Tano Genaro (1913)

El Jaguel by Tipica Criolla La Amonia (1913)

El Argentino by Vicente Loduca (1913)

El Fulero by Quinteto Berto (1914)

El Pollito by Quinteto Criollo Atlanta (1916)

La Cumparsita by Roberto Firpo (1916)

Cara Sucia by Francisco Canaro (1917)

Mi Noche Triste (Lita) by Carlos Gardel (1917)

Pampa by Qrquesta Ferrer-Filipotto (1918)

Beligica by Osvaldo Fresedo (1920)

Pugliese was outspoken in his political opinions and was a communist. These sympathies often brought him into conflict with the government and police. His orchestra was banned from being played on the radio on several occasions. In 1955, Perón had him jailed for six months. He was also jailed by the previous government and later governments. Whenever he was arrested his band would place a red carnation or rose on his piano as a "symbol of absence (símbolo de ausencia)." He was threatened many times during the dark days of the Proceso (1976 to 1983) but as Juan Carlos Copes explains, "he was simply too popular" to "disappear."

Pugliese was outspoken in his political opinions and was a communist. These sympathies often brought him into conflict with the government and police. His orchestra was banned from being played on the radio on several occasions. In 1955, Perón had him jailed for six months. He was also jailed by the previous government and later governments. Whenever he was arrested his band would place a red carnation or rose on his piano as a "symbol of absence (símbolo de ausencia)." He was threatened many times during the dark days of the Proceso (1976 to 1983) but as Juan Carlos Copes explains, "he was simply too popular" to "disappear."

The Basics

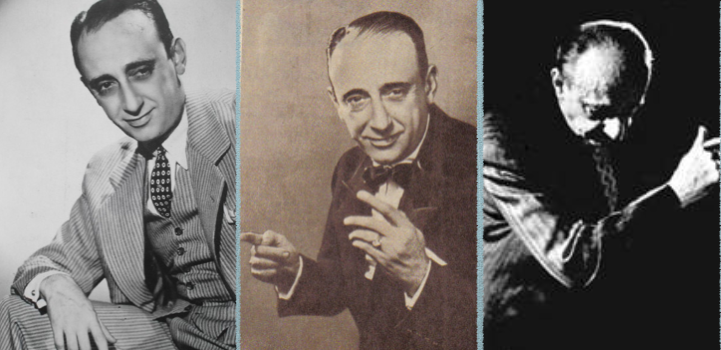

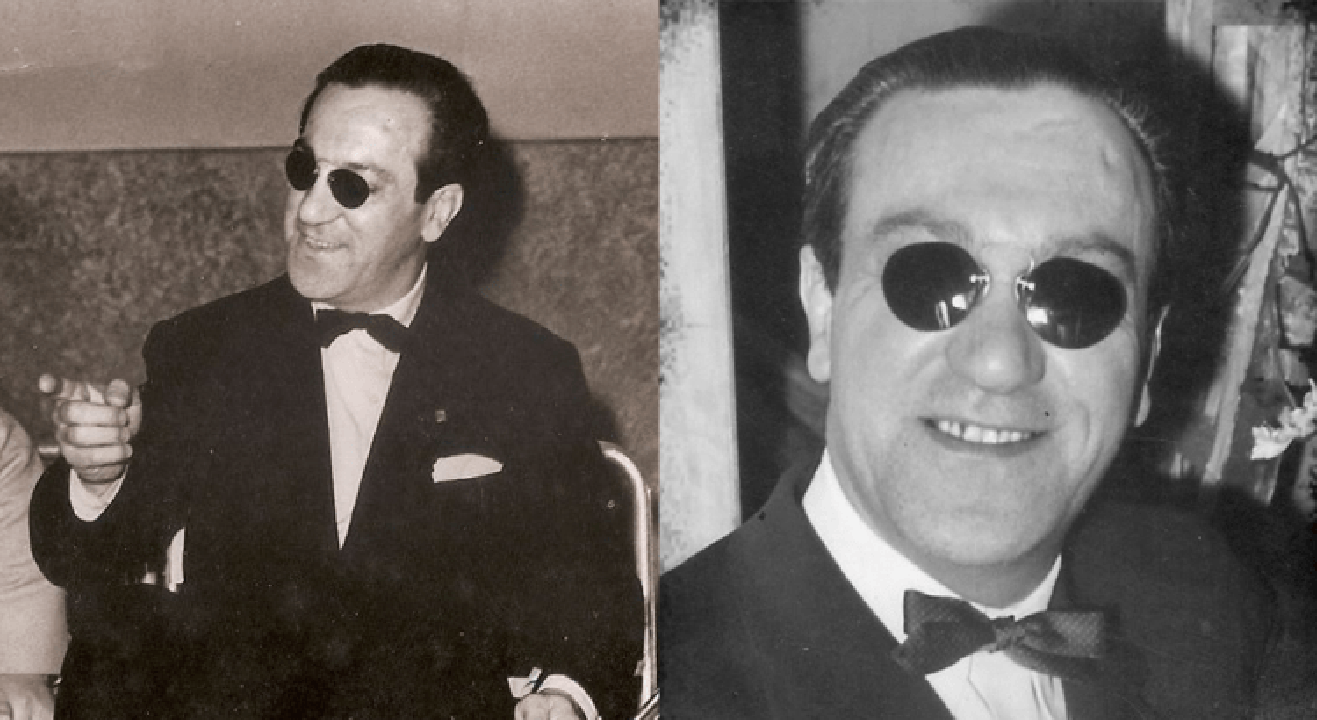

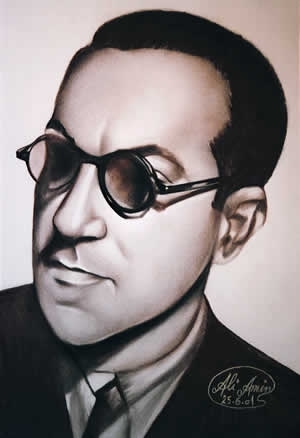

The Basics In 1928, his orchestra was playing at the Florida Cabaret. They had replaced Osvaldo Fresedo's orchestra and it is here that the famous announcer, Príncipe Cubano (The Cuban Prince) (pictured left), anointed d'Arienzo "El Rey del Compás (The King of the Beat)." As d'Arienzo explained it,

In 1928, his orchestra was playing at the Florida Cabaret. They had replaced Osvaldo Fresedo's orchestra and it is here that the famous announcer, Príncipe Cubano (The Cuban Prince) (pictured left), anointed d'Arienzo "El Rey del Compás (The King of the Beat)." As d'Arienzo explained it,  In 1928, he recorded for the first time with his own orchestra, Juan D'Arienzo y Los Siete Ases del Tango. They recorded 44 sides, with the estribillistas: Carlos Dante, Francisco Fiorentino, and, the female singer, Raquel Notar. Other notable members of the orchestra were Ciriaco Ortiz (bandoneon) and Luis Visca (piano). The beat that Príncipe Cubano was commenting on was evident in these recordings and was a return to the beat of the Guardia Vieja period, which many orchestras had abandoned. The beat of the Guardia Vieja movement had a strong driving staccato dance rhythm, D'arienzo's adherence to this would place him in the Canaro school of tango.

In 1928, he recorded for the first time with his own orchestra, Juan D'Arienzo y Los Siete Ases del Tango. They recorded 44 sides, with the estribillistas: Carlos Dante, Francisco Fiorentino, and, the female singer, Raquel Notar. Other notable members of the orchestra were Ciriaco Ortiz (bandoneon) and Luis Visca (piano). The beat that Príncipe Cubano was commenting on was evident in these recordings and was a return to the beat of the Guardia Vieja period, which many orchestras had abandoned. The beat of the Guardia Vieja movement had a strong driving staccato dance rhythm, D'arienzo's adherence to this would place him in the Canaro school of tango. The Tango Cancíon and Guardia Nueva Movements

The Tango Cancíon and Guardia Nueva Movements

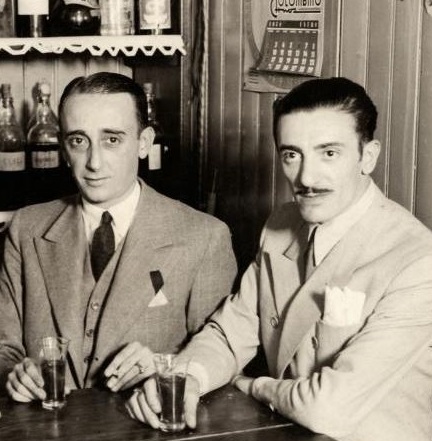

By 1938, d"Arienzo's orchestra was at the height of its popularity. He was just 35 years old, one less than Julio de Caro, but stylistically at the other end of the musical spectrum of tango. His records were selling and they were regularly playing on radio shows. But remember, above, when I made the joke about d'Arienzo being modest? Well, audiences had been becoming bigger and bigger fans of Biagi, and at a concert later that year, after a performance of “Lágrimas and Sonrisas,” the audience clapped until Biagi finally stood up and took a bow. As the story goes, d'Arienzo walked over to him and said, “I’m the only star of this orchestra. You’re fired.”

By 1938, d"Arienzo's orchestra was at the height of its popularity. He was just 35 years old, one less than Julio de Caro, but stylistically at the other end of the musical spectrum of tango. His records were selling and they were regularly playing on radio shows. But remember, above, when I made the joke about d'Arienzo being modest? Well, audiences had been becoming bigger and bigger fans of Biagi, and at a concert later that year, after a performance of “Lágrimas and Sonrisas,” the audience clapped until Biagi finally stood up and took a bow. As the story goes, d'Arienzo walked over to him and said, “I’m the only star of this orchestra. You’re fired.”

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the whole world had been in an economic slump and this included Argentina. But in 1935 Buenos Aires was preparing for the 400th anniversary if its founding as a city. This included building of a 72-meter high Obelisk and the opening of the avenida 9 de Julio. This brought a new energy and optimism to the city.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the whole world had been in an economic slump and this included Argentina. But in 1935 Buenos Aires was preparing for the 400th anniversary if its founding as a city. This included building of a 72-meter high Obelisk and the opening of the avenida 9 de Julio. This brought a new energy and optimism to the city. In 1937, Aníbal Troilo's orchestra debuted with Francisco Fiorentino as the singer. Troilo was a large man and had the nickname "Pichuco." He was an innovator and kept pushing tango into new areas especially once he hired a young bandoneon player named Astor Piazzolla and made him arranger for his orchestra. Troilo was popular with both dancers and the listening public. To this day, his pictures are hanging all over Buenos Aires cafés and restaurants. Listen to his song, "Tinta Roja" below.

In 1937, Aníbal Troilo's orchestra debuted with Francisco Fiorentino as the singer. Troilo was a large man and had the nickname "Pichuco." He was an innovator and kept pushing tango into new areas especially once he hired a young bandoneon player named Astor Piazzolla and made him arranger for his orchestra. Troilo was popular with both dancers and the listening public. To this day, his pictures are hanging all over Buenos Aires cafés and restaurants. Listen to his song, "Tinta Roja" below.