Carmencita dancing milonga in 2000 at 95 Years Old.

To see more videos of her dancing go to my "Favorite Older Milonguero Performances" page.

| Home > Tango Resources > Tangology 101 Blog |

Carmencita dancing milonga in 2000 at 95 Years Old.

To see more videos of her dancing go to my "Favorite Older Milonguero Performances" page.

Canyengue is one of the earliest forms of Tango and was probably the style that was taken over to Paris at the turn of the century. Here is a good demonstration of this style. It is very rhythmic and danced more into the ground than we dance tango today.

The first generation of tango musicians are commonly referred to as "La Guardia Vieja" (The Old Guard). The first Period of "La Guardia Vieja" lasted from approximately 1895 to 1910. These songs are a type of habanera blended with African and European music and are sometimes referred to as "tango-habanera," "tango criollo" or "tango-milonga."

This period saw:

The music originated in the "Rioplatenese" or Río de la Plata region of Argentina and Uruguay. Some of the origins of the music would be candombe, vals criollo, habanera, flamenco, polka, milonga (different from the milonga we know today and was a type of "battle" poetry), mazurka and contradanse. In essence, you had European immigrants with their instruments being influenced heavily by Latin American and African music.

It is true that only about 8,000 black argentines existed out of a population of over 400,000 in 1887, but all it took was a few to have a great impact on tango. The best example of this was Leopoldo Ruperto Thompson. Get this, he was a bass player who played with Firpo, Canaro, Arolas, de Caro and Cobián. Many of the first bandoneon players and guitarists were black. Also, some of the earliest composers of tango including Mendizábal and Carlos Posadas, as well as many of the earliest dancers and teachers.

At this time Tango was played by solo guitar or piano, small ensembles (conjuntos) and municipal marching bands. The ensembles were usually trios and would often consist of some combination of flute, clarinet, guitar and/or violin. The guitar would often play the habanera rhythm while the flute, clarinet and/or vilolin played the melody. Sometimes, these groups would be accompanied by male or female singers. They would play in cafés, beer houses, courtyards of conventillos (poor apartment houses) and also in brothels. The music would also have been played around the city by organitos or organ-grinders who went around the city playing portable player-organs.

Towards the end of this period we also saw the signature instrument of tango, the bandoneon, introduced to the ensembles. The bandoneon was a concertina type of instrument created in Germany for churches that could not afford an expensive organ. It made its way over to Argentina and Uruguay with the huge influx of immigrants.

|

|

During this time, tango begins to take on structure. In 1897, Anselmo Rosendo Menizábal composed, "El entrerriano (The Man from Between the Rivers)" which was the first tango structured in three distinct sections. The 1st and 3rd sections had 16 measures and the 2nd measure had thirty-two measures.

In the early 1900s, many academias and cabarets began to open around the city. Academias were places were people could learn the choreography of tango and other dances. Cabarets were public places where people could dance and play tango. Armenonville, at the corner of Avenida Alvear y Table, was one of the first of these places. Other establishments were also opening and promoting tango like Hansens which was a restaurant/café on Avenida Sarmientos. The picture on the left was taken in March of 1905 at a carnival at the Pabellón de las Rosas (Rose Pavillion), a popular dance venue in Buenos Aires.

In the early 1900s, many academias and cabarets began to open around the city. Academias were places were people could learn the choreography of tango and other dances. Cabarets were public places where people could dance and play tango. Armenonville, at the corner of Avenida Alvear y Table, was one of the first of these places. Other establishments were also opening and promoting tango like Hansens which was a restaurant/café on Avenida Sarmientos. The picture on the left was taken in March of 1905 at a carnival at the Pabellón de las Rosas (Rose Pavillion), a popular dance venue in Buenos Aires.

This period also saw men dancing with other men. The primary reasons for this was that men greatly outnumbered women and so the women had their pick of the men to dance with. So, the men would get together and practice and learn from one another in order to improve so that the could attract the few women dancers. This was a time when women and men could not associate as easily as today.

.jpg)

Many early pioneers of rioplatense tango travelled to Europe including Angel Villoldo, Alfredo Gobbi, and his wife, Flora Hortensia Rodriguez to record ind France and Germany. Below are some of the earliest recordings of tango. These recordings are from vinyl LPs and 78s. I am working on getting them all recorded and posting as much historical information about them as possible.

Between 1906 and 1910, 850,000 immigrants arrived in Buenos Aires and the population grew to 1,500,000, setting the stage for the next period of tango's growth.

“La Morocha” (?)

“La Morocha” (?)

Composer: Enrique Saborido

Performed by: Recording of an orginal Barrel Organ (Organito)

The original sheet music describes the song as "tango criollo." There is some debate about whether or not this or "el choclo" was the first tango to be exported to Europe. Saborido travelled to Paris and was there in 1911 teaching people how to play and dance tango. Of course, this version is an instrumental, but Angel Villoldo did add lyrics to the song.

More on Enrique Saborido: http://www.todotango.com/

More on "La Morocha:" http://www.todotango.com/

"El Sargento Cabral" (1907)

Composer: Manuel O. Campoamor

Performed by: Banda de la Guardia Republicana de Paris

.gif)

The pianist and composer Manuel O. Campoamor numbered all his tangos and "El Sargento Cabral", dating from 1898 or 1899 is number 1.

Campoamor was born on November 7, 1877 in Montevideo, Uruguay, but he grew up in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He learned to play the piano by ear and never learned to write music. He composed tangos from 1898 to 1905 and kept playing piano publicly until 1922, but according to his wife he would still play at home every day until his death in 1941 of Lung Cancer. He is quoted as saying, "I didn't compose any more and don't even think of doing it; I neither have the enthusiasm nor the time to devote to that. Today the output is overwhelming and the number of composers is great. The present generation has adopted a different beat for tango, which is warmly welcome by the public; we, those who feel tango in quite a different way, have to withdraw to allow the new trends to express this new sensitivity."

"El Sargento Cabral" was published in 1899 by Gath & Chaves house where Campoamor worked for 25 years, eventually becoming manager.

It was edited by J. A. Medina e Hijo and it as dedicated to the composer Leopoldo Corretjer. According to the author, this work owes its title to a common occurrence in local dance spots of the time. Following a competition someone from the winning side would exclaim, "We have beat the enemy!" in parody of what Sargent Cabral said shortly before his own death in the battle of San Lorenzo.

The recording of Paris' Republican Band belongs to a series of recordings made specifically for the recording house, Gath & Chaves. They sent several pioneers of rioplatense tango to Europe including Angel Villoldo, Alfredo Gobbi, and his wife, Flora Hortensia Rodriguez to record because there was no recording studio in Buenos Aires.

Campoamor also worked as a pianist in the famous house of Maria "La Vasca" which can still be found at the corner of Carlos Calvo Street and Jujuy Street.

For more information on Campoamor visit: http://www.todotango.com/

"Mordeme la oreja izquierda" (Bite my left ear) (1908)

"Mordeme la oreja izquierda" (Bite my left ear) (1908)

Composer: Eugenio M. de Alarcon

Performed by Banda Española

This edition of the tango dates from 1906 and belongs to the composer himself, who dedicated it "Al amigo Cesar H. Colombo" (To the friend Cesar H. Colombo). It has the odd subtitle "Canto de dos ruiseñores" (A song of two nightingales) and the classification of "tango criollo." A footnote on the cover warns that any sample that does not have the author's signature should be considered a falsification.

Alarcon, director of the national theater orchestra, enjoyed using many italianisms when indicating how to express the music; on this piece one can see words such as "expressivo", "legatissmo", "scelti", "ben ritmato", etc.

For more information: http://www.todotango.com/

"El Club Z" (1908)

"El Club Z" (1908)

Composer: Anselmo Rosendo Mendizabal

Performed by: Orquesta del Teatro Apolo Dir: Enrique Cheli

The "Z Club" was composed of a group of revelers headed by Esteban Banza and J. Guidobono. This was an exclusive group formed by forty individuals with the sole purpose of organizing a monthly dance for its members. This group existed from the end of the nineteenth century to the first decade of the twentieth century. The dances were generally held in the house of Maria La Vasca, and it was rented for the entire night for 3 pesos per hour per person. The Afro-Argentine pianist and composer Mendizabal was the usual musician, both as a soloist as well as when he played with his band, which was composed of two violins, a flute, a piano and two guitars. Mendizabal composed many tangos including "El Club Z" where an instrumental call and response surmounts a habanera accompaniment.

Due to prejudices of the time, Mendizabal signed his tangos with the pseudonym "A. Rosendo". The original score included in this anthology is edited by the author by the musical press Ortelli Hnos. Has the dedication, "A los distinguidos socios del Z Club" (To the distinguished members of the Z Club).

For more information: http://www.todotango.com/english/crea...

“El Pechador” (1909)

“El Pechador” (1909)

Composed by: Angel Gregorio Villoldo

Performed by: Linda Thelma (canto) y Arturo de Siano (piano)

Edited by the house David Poggi e Hijo, it was dedicated by Villoldo “Al celebrado autor nacional don Nemesio Trejo” (to the celebrated national author Mr. Nemesio Trejo), who was the singer and author of comic sketches (1862-1916); it was a popular tango in its time and it was also recorded by Alfredo Gobbi.

Like most, if not all, of Villoldo’s lyrics they are written in the first person and exalt the virtues of the compadrito. Although it may seem inappropriate this title is sung by a woman, the singer Linda Thelma, who has deep roots in Spanish tiples [I have no idea what this is]. She was accompanied on many an occasion by Villoldo himself while recording. Arturo de Siano, a musician who plays with Linda Thelma in this version, was a prominent musician in the theater.

More info on Angel Gregorio Villoldo: http://www.todotango.com/english/creadores/avilloldo.html

More info on Linda Thelma: http://www.todotango.com/english/creadores/lthelma.asp

“El Purrete (The Kid)” (1909)

“El Purrete (The Kid)” (1909)

Composed by: Jose Luis Roncallo

Performed by: Banda de la Policía de Beunos Aires Dir: Mtro. A Rivara

Basically, all bands incorporated tangos into their repertoires during the first two decades of the century. You can hear the habanera being heavily dramatized as the cymbals clash during the song. These types of bands reached their peak during these years as is demonstrated by the elevated number of recordings made. Some of the most well-known ones include: the 1st Infantry Regiment, the 5th Infantry regiment, the Atlanta, and the Buenos Aires Police.

“El Purrete”, edited by Breyer Hnos. and dedicated to “El Senor Eduardo Oliveri” (Mr. Eduardo Oliveri) was the first tango written by this author. His style was methodical and consistent with a musician trained in a conservatory. According to unverified claims, the song dates from 1901 and the score dates from some time after, 1903 to 1904.

“El Purrete”, edited by Breyer Hnos. and dedicated to “El Senor Eduardo Oliveri” (Mr. Eduardo Oliveri) was the first tango written by this author. His style was methodical and consistent with a musician trained in a conservatory. According to unverified claims, the song dates from 1901 and the score dates from some time after, 1903 to 1904.

“La Bicicleta” (1909)

Composer: Angel Gregorio Villoldo

Performed by: Angel Villoldo (canto y castañuelas) y Manuel O. Campoamor (piano)

The primitive form of singable rioplatense tango suffered great influences from Spanish zarzuela tango. This is very clearly detectable in the version of “La bicicleta” by Angel G. Villoldo. It has a piano accompaniment by Manuel O. Campoamor purely for melodic purposes as well as castanets played by Villoldo.

Cycling and pelota vasca were the favorite sports during 1895 and 1910, where one could find extensive bicycle caravans traveling to be exhibited in the forests of Palmero after first riding in the city center.

According to Robert Farris Thompson, "Villoldo's 'La bicicleta' (The Bicycle) of 1909 began, nobly, to mix cultures. From the famus black payador Gabino Ezeiza, Villoldo borrows jump-cuts from singing to speech. He hits certain words, like damas and ramas, with flamencolike trills, Arabized melismas that add savor to rhyme. And while he's singing, Villoldo plays castanets!"

More info on Villoldo: http://www.todotango.com/english/creadores/avilloldo.html

More info on Campoamor: http://www.todotango.com/english/crea...

“El Porteñito” (1909)

Composer: Angel Gregorio Villoldo

Performed by: Andrée Vivianne (canto) y orquesta

More info on Villoldo: http://www.todotango.com/english/creadores/avilloldo.html

“Gran Hotel Victoria” (1910)

“Gran Hotel Victoria” (1910)

Composer: Feliciano Latasa

Performed by: Estudiantina Centenario (trio de bandurrias y guitarra) Dir: Vicente Abad

For more information: http://www.todotango.com/english/biblioteca/cronicas/leyenda_Hotel_Victoria.asp

"Joaquina" (1911)

Composer: Juan Bergamino

Performed by: Manuel O. Campoamor (solo piano)

Below are articles on some of the most famous Tango orchestras including biographies, videos and their most popular songs:

"La Guardia Nueva" (The New Guard) period lasted from approximately 1925 to 1935. The new musicians developing during this period would be known as "The 1925 Generation."

This period saw:

El Cuatro (The Four)

During this period, the habanera influence began to fade and the tempo of the music slowed down. In "Tango: The Art History of Love," tango guitarist Ubaldo de Lío says, "The earliest form of tango was a type of habanera. The tango-milonga then followed. After that came 'the four,' four quarter-notes per measure. We still ask ourselves who invented 'the four.' Some say Canaro, others say Firpo, a few claim de Caro." "The four" consists of 4 equal quarter notes (beats) with 2 strong beats (down beats) and 2 weak beats (up beats). In dancing, we usually step on beats 1 and 3 (the down beats) and not 2 and 4 (the up beats) unless we using traspíe or double-timing.

From Robert Farris Thompson's "Tango: The Art History of Love:"

"The four" arrived in force in the 1920s, with Firpo, Canaro, and de Caro. Important changes in harmony and phrasing came with it: polyphony and counterpoint emerged with de Caro. Tango was in a state of creative ferment. Black swing and black imporvisatin met innovations evolving within the Western-oriented tradition. The black composer Mendizábal, we recall, had designed the early structure of tango, involving a first and third part of sixteen bars each with a bridge of thirty-two bars in between. Now de Caro and his peers swept this away: 'After 1925 nobody writes [tangos] in three parts any more; sometimes introductions, bridge passages, and codas are added.' The trend was now to structure in two parts, doubled in execution: A B A B.

In the late 20s and early 30s, more classically trained musicians began to join and form orchestras and were influencing the largely self-taught musicians of the previous generation. Some of the older generation would say things such as "They have turned tango into church music," because they were working more with melody and harmony than rhythm.

Julio de Caro

Julio de Caro

The most famous of these was the violinist Julio de Caro who put together an orchestra which included the bandoneonista Pedro Laurenz. He still retained an element of tango's street beginnings, but with more elegance and complex structure. He also slowed tango down even more. This new style combined with Tango Cancíon and the popularity of records meant that a larger "listening" audience was growing rather than a "dancing" audience. Orchestras no longer had to depend on dancers to pay the bills and began creating music that was not popular with dancers and tango as a dance sharply declined.

After this period, most orchestras were from one of two camps, the traditionalists or evolutionists. The traditionalists would consist of orchestras such as Francisco Canaro, Juan D'Arienzo, Edgardo Donato and Rodolfo Biagi. The evolutionists would consist of orchestras such as of Osvaldo Pugliese, Aníbal Troilo, Carlos di Sarli, Osvaldo Fresedo and Pedro Laurenz. Not that the traditionalists did not evolve as well, they just did not take it as far.

With the advent of silent films, the best tango musicians were sought after to play for the movies. For less popular films, one pianist would do, but for more popular films sometimes a trio, quartet or a sexteto típico would be employed.

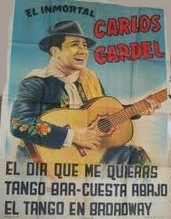

Tangos were also a popular subject for films and the tango stars of the day, including Gardel, often starred or made appearances in them.

Tangos were also a popular subject for films and the tango stars of the day, including Gardel, often starred or made appearances in them.

Tango orchestras were also very much in demand for the new medium of radio and would often play live and have their own weekly shows.

In the 1910s, as orchestras became more in demand to play large dances and festivals, their sizes ballooned to more than 1 dozen musicians. For a festival in 1921, Francisco Canaro presented an orchestra of 12 bandoneons, 12 violins, 2 cellos, 2 double-basses, 2 pianos, 1 flute and 1 clarinet. By the mid-1920s, the popularity of the microphone had made it so that most orchestras took the form of sextetos típicos.

Lorenzo by Julio de Caro con Luis Diaz (1926)

Amurado by Juan Felix Maglio (1927)

Flores Negras by Julio de Caro (1927)

Adios Muchachos by Orquesta Tipica Victor (1927)

Viejo Ciego by Francisco Canaro (1928)

Quejas de Bandoneon by Roberto Firpo (1928)

Felicia by Edgardo Donato (1930)

Fruta Prohibida by Orquesta Tipicia Brunswick (1931)

El Huracan by Edgardo Donato (1932)

Milonga Sentimental by Francisco Canaro (1933)

Ventarron by Orquesta Tipica Victor (1933)

Vida Mia by Osvaldo Fresedo (1933)

Siempre es Carnaval (1934)

Poema by Francisco Canaro (1935)

The second part of the Guardia Vieja period lasted from approximately 1910 to 1935. I say approximately because the styles and changes of this period blended very smoothly with the preceding and following periods. It is not as if on January 1, 1910 people started composing and playing differently.

This period saw:

Tangomania

Up until the early 1910s, tango had largely been a past time of the lower classes. It had been played and danced in cafés, bordellos, restaurants, conventillos but not in the salons of the elite. After Tangomania swept Europe and the US, this all changed and tango began to be embraced by the middle and upper classes of Buenos Aires. It is impossible to understate the popularity of Tango in Europe. It was the rage of the salons and made headlines in newspapers.

Enrique Saborido, the composer of many tangos including "La Morocha," also travelled to Europe to teach people how to properly play tango and ended up also teaching people to dance:

"The marquise Reské, widow of the famous tenor Jean Reské, was willing to popularize Argentine tango among the French. It was around 1911 and I accepted such formal invitation; when in Paris, at the beginning I devoted to teaching tango playing, so that it would be correctly performed. As I had spare time and I had noticed that the high society people were really interested in it, I taught them how to dance it.

One night at the marquise palace where a reception was held I organized, with the approval of the attendance, a pericón (traditional Argentine dance) whose steps proved to be very attractive for everybody and were warmly applauded.

On another occasion I was appointed referee to demonstrate that the forlana was not more decent than tango; the dissent was even reflected in the chronicles at the papers and the Catholic paper "Le Gaulois" finally regarded tango as a beautiful graceful dance.

Thereafter the outbreak of war forced me to come back to Buenos Aires."

Acceptance

It is also impossible to understate the influence that Europe's acceptance, particularly France's, had on Buenos Aires. It is joked that, porteños were Italians that spoke Spanish, thought they were British and wished they were French. Anyone who visits Buenos Aires cannot deny the influence of French architecture.

Orquesta Tîpicas

Orquesta Tîpicas

In 1911, Vincente Greco was asked to record some tangos by Columbia and he created the first Orquesta Típica Criolla. Over time the "criolla" was dropped from the name. The original Orquesta Tîpicas were sextets which consisted of two bandoneons, two violins, a double bass and a piano (sometimes a guitar or flute were substituted). Eventually they grew to include a string section (with violins, viola, and cello), a bandoneón section (with 3 or more bandoneons), and a rhythmic section (with piano and double bass). The piano was first added by Roberto Firpo in 1913 and the double bass by Francisco Canaro in 1917.

Around 1916, Firpo re-wrote a march by Gerardo Mattos Rodriguez as a tango. It would become the most famous of all tangos, "La Cumparsita."

Carnivals

Carnivals were huge events where massive amounts of people would come to hear the most popular orquestas of the day. Orquestas would save their best new pieces to debut them at the carnivals. Carnivals were very popular with dancers. Many dance academias would advertise to dancers, "Come and learn the best new figures for the carnival."

Tango Canción

Up to this point, tango lyrics had been dark, but humorous. In 1917, Carlos Gardel recorded Pascual Contursi's "Mi Noche Triste." Now Contursi could have meant the lyrics to be ironic but Gardel sang the song with melodramatic longing and sadness. This song struck a cord with the newly arrived immigrants, who were missing their countries, families and wives and was hugely successful, launching a new genre "tango-canción." Tango-canción was full of drama, sentimentality, sadness and nostalgia.

In 1920, the first tango written as a song, "Milonguita." Up until that time, tangos had been written as music first and then lyrics added later. This was the first time that a song was written as lyrics first. It was turned into a movie in 1922 and was the first to feature the theme of the poor, country girl who leaves home to go to the big city of Buenos Aires and becomes a prostitute.

In 1920, the first tango written as a song, "Milonguita." Up until that time, tangos had been written as music first and then lyrics added later. This was the first time that a song was written as lyrics first. It was turned into a movie in 1922 and was the first to feature the theme of the poor, country girl who leaves home to go to the big city of Buenos Aires and becomes a prostitute.

Women's Orquestas

Paquita Bernardo was the first professional female bandoneon player and Carlos Gardel said she was, "the only woman who has mastered the macho character of the bandoneon." The debuted her sextet in 1921. There were many women's orquestas and they were popular between 1920 and into the early 1930s. They often played in confiterías, cafés, bars, for weddings and parties. To the best of my knowledge, no women's Orquesta was ever recorded, but there is some film footage of one from the 1933 film, "Tango!"

Paquita Bernardo was the first professional female bandoneon player and Carlos Gardel said she was, "the only woman who has mastered the macho character of the bandoneon." The debuted her sextet in 1921. There were many women's orquestas and they were popular between 1920 and into the early 1930s. They often played in confiterías, cafés, bars, for weddings and parties. To the best of my knowledge, no women's Orquesta was ever recorded, but there is some film footage of one from the 1933 film, "Tango!"

“Cara Sucia” (1917)

“Cara Sucia” (1917)

Composer: Francisco Canaro y 'El Negro' Casimiro Alcorta

Performed by: Francisco Canaro

Some song titles and lyrics were changed because the originals were so vulgar. "Concha Sucia" was a traditional song believed to have been composed by 'El Negro' Casimiro Alcorta, a black violin player from the earliest days of tango. The title literally translates to "Dirty Shell," but concha (shell) was a common, obscene term for vagina. Canaro registered this tango, under his own name, and changed the song title to "Cara Sucia" in 1916. Canaro is believed to have done this with several of the old tangos. The name change was probably to conform to the changing audience of tango, which was including more women and the middle class.

More on Francisco Canaro: http://www.todotango.com/...

Songs of this Period

Rosendo by Orquesta Tipica Criolla (1912)

Don Juan by Alfredo Gobbi

Miniquito by Flora Gobbi (1911)

La Montura by Genaro Exposito (1912)

Armenonville by Juan Pacho Maglio (1912)

Venus by Juan Pacho Maglio (1912)

El Estribo by Vicente Greco (1912)

El Apache Argentino by Arturo A. Mathon (1913)

El Choclo by Orquesta Tipica Portena (1913)

Mi Preferido by Orquesta Criolla Domingo Biggeri (1913)

Region Campera by Quinteto Criollo El Aleman (1913)

Pura Uva by Quinteto Garrote (1913)

Recuerdos de Zambonini by Quinteto Tano Genaro (1913)

El Jaguel by Tipica Criolla La Amonia (1913)

El Argentino by Vicente Loduca (1913)

El Fulero by Quinteto Berto (1914)

El Pollito by Quinteto Criollo Atlanta (1916)

La Cumparsita by Roberto Firpo (1916)

Cara Sucia by Francisco Canaro (1917)

Mi Noche Triste (Lita) by Carlos Gardel (1917)

Pampa by Qrquesta Ferrer-Filipotto (1918)

Beligica by Osvaldo Fresedo (1920)

Osvaldo Pedro Pugliese (Buenos Aires, December 2, 1905 – July 25, 1995) was an orchestra leader, composer and pianist.

He was known for his dramatic and passionate arrangements while still keeping the strong walking beat of salon tango. His music walked a fine line between the dance hall and concert hall. The greatest musicians of the time wanted to work with Pugliese.

One could speak, with total justice, of compositions before and after Pugliese's "Recuerdo" and the instrumentalists before and after "Recuerdo." - Horacio Ferrer

He composed his first tango "Recuerdo" in 1924 when he was only 19 years old. The title was originally "Recuerdo para mis amigos" (Memory for my friends) and was an homage to his friends that he used to hang out with in the cafe. This song is often described as a milestone of tango composition for its melodic structure and its complex density. "Recuerdo" shows Pugliese's knowledge of European classical music and his commitment to the streets of Buenos Aires, as de Caro had previously. It is no wonder that de Caro was the first orchestra to record the song.

Pugliese is often played later in the evening when the dancers want to dance more slowly, impressionistically and intimately. While being able to dance well to Pugliese's music is the mark of a truly accomplished dancer, his music is very challenging for new dancers.

Pugliese was outspoken in his political opinions and was a communist. These sympathies often brought him into conflict with the government and police. His orchestra was banned from being played on the radio on several occasions. In 1955, Perón had him jailed for six months. He was also jailed by the previous government and later governments. Whenever he was arrested his band would place a red carnation or rose on his piano as a "symbol of absence (símbolo de ausencia)." He was threatened many times during the dark days of the Proceso (1976 to 1983) but as Juan Carlos Copes explains, "he was simply too popular" to "disappear."

Pugliese was outspoken in his political opinions and was a communist. These sympathies often brought him into conflict with the government and police. His orchestra was banned from being played on the radio on several occasions. In 1955, Perón had him jailed for six months. He was also jailed by the previous government and later governments. Whenever he was arrested his band would place a red carnation or rose on his piano as a "symbol of absence (símbolo de ausencia)." He was threatened many times during the dark days of the Proceso (1976 to 1983) but as Juan Carlos Copes explains, "he was simply too popular" to "disappear."

During the Golden Age, many dancers would follow their favorite orchestras around like soccer fans of today. No fans were more dedicated than Pugliese's, some of whom would copy his haircut, glasses and suits. For some reason, some would wear band-aids forming a cross on their right cheeks. The women who followed Pugliese often wore Shanghai inspired dresses with slits cut on both sides along with anklets and high heels.

"La Yumba" was another of Pugliese's major hits. It was recorded in 1946 and showed his respect for the early black musicians of tango. As mentioned before, Pugliese took tango to a new level but did not discard its roots in the streets of BA. He stated once that he was inspired to write "La Yumba" by a young black pianist, "I kept my ears open. I remember, around 1930, a young black pianist who used to hang with us. He played by ear in tango dance halls. He was marvelous. We loved this black guy. Me and him used to play, four hands on a keyboard. In Ki-Kongo, where many of the blacks of BA came from, yumba meant "to dance!" Candombe musicians and artists would yell "Oyeye yumba!" (Sing it! Dance it!).

Live Perfomances at the El Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires from 1985:

The Basics

The Basics

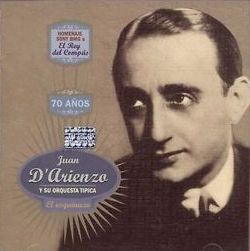

Juan d’Arienzo (December 14, 1900-January 14, 1976) was a violinist, pianist, band leader and composer. His nickname was “El Rey del Compas” (The King of the Beat). D’Arienzo was born on 14 December 1900 in the Buenos Aires neighborhood of Balvanera. His orchestra is considered one of the "Big Four" orchestras of Argentine tango, along with: Carlos di Sarli, Anibal Troilo, and Osvaldo Pugliese. They recorded over 1,000 tangos, valses, and milongas. He worked with the following key singers: Alberto Echagüe, Héctor Mauré, Alberto Reynal, Armando Laborde, Jorge Valdez, and Mario Bustos.

D'Arienzo began by playing jazz, at the age of 15, but was beginning to play tangos by the age of 18. He was a member of a youth orchestra which also featured Ángel d'Agostino on piano. In his early years, he played, as did many musicians of that period, in theaters playing music for silent films and in the cabarets including: Abdullah, Palais de Glace, Florida, Bambú, Marabú, Empire, Chantecler, Armenonville. He played in many small orchestras, and loved the nightlife. He once wrote, "We were beginning to live only at four in the morning... At the cabarets, you played all night through, people danced, had fun, they stayed til sunrise and the muscicians strained themselves."

1928 to 1935

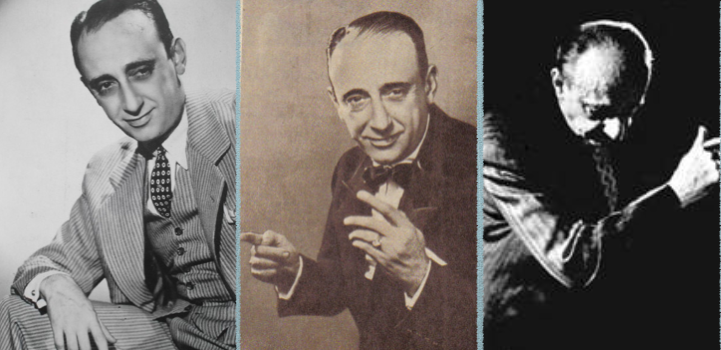

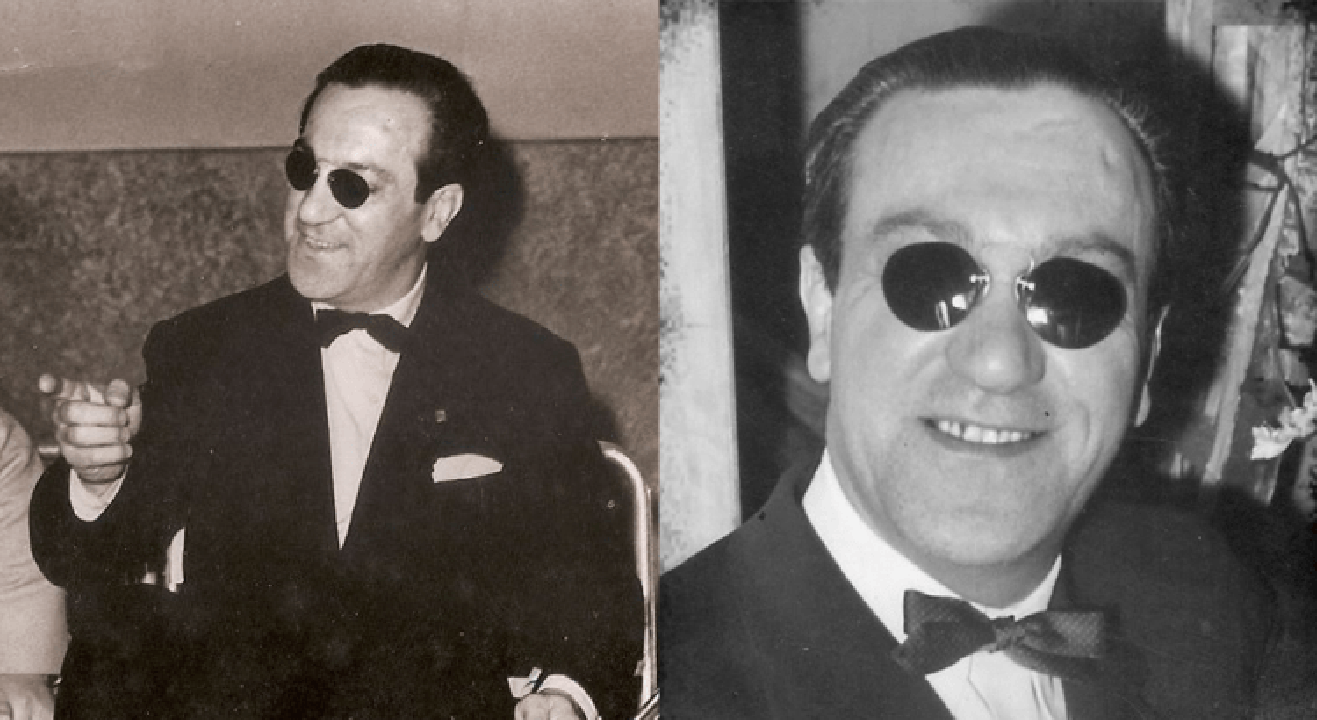

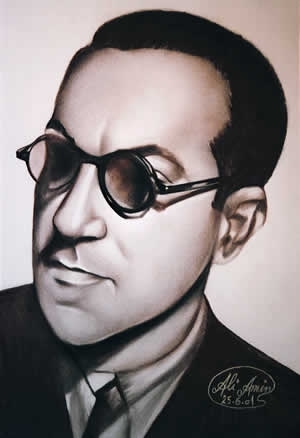

In 1928, his orchestra was playing at the Florida Cabaret. They had replaced Osvaldo Fresedo's orchestra and it is here that the famous announcer, Príncipe Cubano (The Cuban Prince) (pictured left), anointed d'Arienzo "El Rey del Compás (The King of the Beat)." As d'Arienzo explained it,

In 1928, his orchestra was playing at the Florida Cabaret. They had replaced Osvaldo Fresedo's orchestra and it is here that the famous announcer, Príncipe Cubano (The Cuban Prince) (pictured left), anointed d'Arienzo "El Rey del Compás (The King of the Beat)." As d'Arienzo explained it,

"Mine was always a tough orchestra, with a very swinging, much nervous, vibrant beat. And it was that way because tango, for me, has three things: beat, impact and nuances. An orchestra ought to have, above all, life. That is why mine lasted more than fifty years. And when the Prince gave me that title I thought that it was OK, that he was right."

In 1928, he recorded for the first time with his own orchestra, Juan D'Arienzo y Los Siete Ases del Tango. They recorded 44 sides, with the estribillistas: Carlos Dante, Francisco Fiorentino, and, the female singer, Raquel Notar. Other notable members of the orchestra were Ciriaco Ortiz (bandoneon) and Luis Visca (piano). The beat that Príncipe Cubano was commenting on was evident in these recordings and was a return to the beat of the Guardia Vieja period, which many orchestras had abandoned. The beat of the Guardia Vieja movement had a strong driving staccato dance rhythm, D'arienzo's adherence to this would place him in the Canaro school of tango.

In 1928, he recorded for the first time with his own orchestra, Juan D'Arienzo y Los Siete Ases del Tango. They recorded 44 sides, with the estribillistas: Carlos Dante, Francisco Fiorentino, and, the female singer, Raquel Notar. Other notable members of the orchestra were Ciriaco Ortiz (bandoneon) and Luis Visca (piano). The beat that Príncipe Cubano was commenting on was evident in these recordings and was a return to the beat of the Guardia Vieja period, which many orchestras had abandoned. The beat of the Guardia Vieja movement had a strong driving staccato dance rhythm, D'arienzo's adherence to this would place him in the Canaro school of tango.

"Acordate Lo Que Fuiste" by Juan d'Arienzo (1928)

In 1933, he appears playing violin with his orchestra in the movie, "Tango." This was the first Argentine film recorded with sound.

1935 to 1939 - The D'Arienzo Revolution

In order to understand, why d'Arienzo was such a big deal, we have to look at what had been going on in regards to tango music at that time.

The Tango Cancíon and Guardia Nueva Movements

The Tango Cancíon and Guardia Nueva Movements

In the mid-1920s, tango music had experienced a change with the emergence of the Guardia Nueva (New Guard) movement. During this period, more classically trained musicians began to join and form orchestras, and were influencing the largely self-taught musicians of the previous generation. Some of the older generation would say things such as "They have turned tango into church music," because they were working more with melody and harmony than rhythm. They were more avante-guard, focusing on robust, complex arrangments and a slower tempo, than that of the Guardia Vieja period.

This, along with the Tango Cancíon (Singing Tango) movement from the 1910s, meant that tango could depend on a larger audience than just tango dancers. They could play at concert halls and sell records without worrying about dancers. Tango dancing did not "die" during this time period, but it did decrease in stature and many people abandoned dancing tango, because most of the music being produced did not facilitate dancing. To understand this, let's listen to some music.

First is a typical song in the Guardia Vieja style, Francisco Canaro's "Viejo Ciego." Technically it was recorded in 1928, during the Guardia Nueva Period, but it is in the style of the Guardia Vieja period. These periods did not have sharp lines, where everyone just changed suddenly and some orchestras such as Canaro, Donato, and OTV continued playing music in the Guardia Vieja style even during the Guardia Nueva period.

"Viejo Ciego" by Francisco Canaro (1928)

Another popular style of tango at this time was Tango Cancíon, which featured the singer over the music. Tango Cancion was born, in 1917, with Gardel's recording of "Mi Noche Triste." It usually consisted of just a guitar and a singer, featuring melodramatic and sad lyrics. Dancers were not the primary concern with Tango Cancíon. Here is an example by Carlos Gardel called "Caminito" from 1926.

"Caminito" by Carlos Gardel (1926)

And finally, here is an example of a typical song from the Guardia Nueva period, by Julio de Caro called, "Flores Negras." As you can hear, it is very complicated and with no clear rhythmic beat for dancing. It is beautiful music and great for listening, but not at all for dancing tango. This caused a serious decline in tango dancing during this period.

"Flores Negras" by Julio de Caro (1927)

1935 to 1939 - The D'Arienzo Revolution

In the early 1930s, d'Arienzo's return to the clear, staccato rhythms of the Guardia Vieja period, gained him a following. And, in 1935, he returns to the recording studio and was a huge success. In later years, d'Arienzo would comment on the Guardia Nueva movement, by writing:

"Young people like me. They like my tangos because they are rhythmic, nervous up-tempos. Youth is after that: happiness, movement. If you play for them a melodic tango and out of beat, surely they won't like it. That's what happens. Now there are good musicians and great orchestras that think that what they play is tango. But it is not so. If they don't have timing there's no tango. They think they can make popular a new style and perhaps they can be lucky, but I keep on thinking that if there is no beat there is no tango. As professionals I have respect for them all. But what they dig is not tango."

Also, on the Tango Cancíon movement:

"In my point of view, tango is, above all, rhythm, nerve, strength and character. Early tango, that of the old stream (guardia vieja), had all that, and we must try not to ever lose it. Because we forgot that, Argentine tango entered into a crisis some years ago. Putting aside modesty, I did all was possible to make it reappear. In my opinion, a good part of the blame for tango decline is on the singers. There was a time when a tango orchestra was nothing else but a mere pretext for the singers. The players, including the leader, were no more than accompanists of a somewhat popular star…

Furthermore, I tried to rescue for tango its masculine strength, which it had been losing through successive circumstances. In that way in my interpretations I stamped the rhythm, the nerve, the strength and the character which distinguished it in the music world."

From these two quotes, you can clearly tell how he felts about these movements, and also, what a modest person he was ;-). He once said, "With me one hundred thousand tango orchestras and neighborhood clubs flourished."

Of course, d'Arienzo did work with many great singers such as Hector Maure, Alberto Echague and Jorge Valdez and sometimes did put them out front. He also made himself somewhat of a star and loved to enthusiastically direct the orchestra during live performances. Below are some live videos of his orchestra from the 1960s. D'Arienzo said of his direction:

"When I direct I am justifiably natural. And I transform. As I direct I take what I feel. Simultaneously I pass on my feelings to the musicians and they, to the public... Before I directed with the baton, now with my own hands: they are more expressive.

Do not think that this is just for the public to see - it is used as a defence by me. I use it well. A look implies a mistake by someone, something that is not played well. They are used by me as a course when I see a loose element, or someone is distracted. I encourage and demand that you be aware, and encourage you with enthusiasm."

Of course, not everyone liked d'Arienzo. Many of the devotees of these movements, saw this turn to the strong beat, as simplistic, regressive and as a serious step backwards for tango music. But the dancer's loved it and between 1935 and 1939, he recorded 116 sides and sold more than Canaro and Troilo combined. In fact, his records were so popular that people were buying little else. Supposedly, some record stores required that you buy something else, in order to by one of his records.

Unfortunately, no masters from that period remain. Everything we listen to today are recordings of 78s and LPs. So, let's listen to "Hotel Victoria." It was recorded during his first recoding session, in July of 1935. Lidio Fasoli is on piano. It is a solid song and clearly shows a return to the Guardia Vieja rhythm, but is nothing "special." But, contrast this to "Flores Negras" and you can see why dancer's responded to d'Arienzo.

"Hotel Victoria" by Juan d'Arienzo (1935)

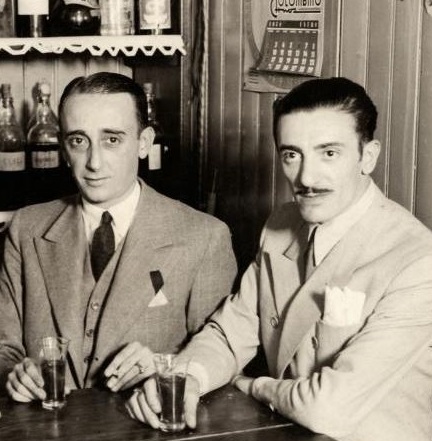

D'Arienzo and Biagi

The defining moment of d'Arienzo's career came in 1935 when he added Rodolfo Biagi as the pianist for his Orchestra. Biagi had just returned from working overseas and d'Arienzo had grown tired of Fasoli showing up late.

Together d'Arienzo and Biagi created his signature driving staccato sound. Soon after, Biagi began writing new arrangements of the songs, creating an even more staccato, uptempo sound than that of the Guardia Vieja. They also increased the orchestra size by increasing both the violins and bandoneons to five each. This filled the songs with a, thus unparalled, aggressive energy that dancers and listeners loved. Let's listen to their first recording together "Nueve de Julio."

"Nueve de Julio" by Juan d'Arienzo (1935)

Ok, so a style is developing, but what makes Biagi so special, as a piano player? Why was he given the nickname "Manos Brujas (Witchy/Magical Hands). Let's listen to another song from two years later, their interpretation of the seminal piece "El Choclo." Here, we will hear his magical hands at work connecting the phrases and adding little accents.

"El Choclo" by Juan d'Arienzo (1937)

By 1938, d"Arienzo's orchestra was at the height of its popularity. He was just 35 years old, one less than Julio de Caro, but stylistically at the other end of the musical spectrum of tango. His records were selling and they were regularly playing on radio shows. But remember, above, when I made the joke about d'Arienzo being modest? Well, audiences had been becoming bigger and bigger fans of Biagi, and at a concert later that year, after a performance of “Lágrimas and Sonrisas,” the audience clapped until Biagi finally stood up and took a bow. As the story goes, d'Arienzo walked over to him and said, “I’m the only star of this orchestra. You’re fired.”

By 1938, d"Arienzo's orchestra was at the height of its popularity. He was just 35 years old, one less than Julio de Caro, but stylistically at the other end of the musical spectrum of tango. His records were selling and they were regularly playing on radio shows. But remember, above, when I made the joke about d'Arienzo being modest? Well, audiences had been becoming bigger and bigger fans of Biagi, and at a concert later that year, after a performance of “Lágrimas and Sonrisas,” the audience clapped until Biagi finally stood up and took a bow. As the story goes, d'Arienzo walked over to him and said, “I’m the only star of this orchestra. You’re fired.”

"Lagrimas y Sonrisas" by Juan d'Arienzo (1936)

Some doubt the story surrounding Biagi's firing, and it very well may not be true, but I do find it interesting that Biagi recorded a far superior version of "Lágrimas y Sonrisas" three years later featuring some "standing ovation" worthy piano playing.

"Lagrimas y Sonrisas" by Rodolfo Biagi (1941)

However, this split did not seem to slow either of them down. In just two short months, Biagi put together a full orchestra and signed a record contract and a radio contract. D'Arienzo replaced Biagi with Juan Polito, and was back in the recording studio just two weeks later. D'Arienzo often said, "The foundation of my orchestra is the piano. I regard it as irreplaceable." Juan Polito might not have been Biagi, but he was pretty close and D'Arienzo continued down the path that he and Biagi had developed. Then two years later, Polito would be replaced with Fulvio Salamanca. Here are the major piano players that played with d'Arienzo.

| Pianist | Years in Orchestra | Recordings |

|---|---|---|

| Lidio Fasoli | 1935 | 10 |

| Rodolfo Biagi | 1935-1938 | 66 |

| Juan Polito | 1938-1940 | 40 |

| Fulvio Salamanca | 1940-1957 | 200+ |

Clint and Shelley's Performance to D'Arienzo:

Popular Songs:

Juan D'Arienzo Practice Playlist

Resources for this Article:

Learn more about Juan d'Arienzo:

Carlos di Sarli (January 7, 1903 – January 12, 1960) was an Argentine tango musician, orchestra leader, composer and pianist. He was born in the town of Bahía Blanca and later wrote one of the most famous tangos of all time of the same name. He composed his first tango in 1919, "Meditación" which was never recorded.

In 1923, he moved to Buenos Aires and started his career playing in Osvaldo Fresedo's orchestra. By 1927, di Sarli started his first sextet. He paid homage to Fresedo by composing the song, "Milonguero Viejo" and dedicating it to Fresedo.

He is known for his smooth, clean-sound and yet powerful arrangements. His songs are often played in Tango classes and at Milongas because of their easy, danceable rhythm while being complex enough for advanced dancers to enjoy. He respected both the melody and the rhythm of Tango. His music has also been described as lyrical and playful.

The rhythms of an orchestra tell dancers how to move. d'Arienzo inspires you to make flashy figures. [But] dancing to di Sarli, you'll walk and you'll stop, making elegant pauses, because the sound of di Sarli is "downtown." - Néstor Fernández

The peak of his career was in the 1940s, but he was always well respected and popular until his death in 1960 as demonstrated by his nickname, "El Señor del Tango" (The Lord of Tango). He worked with some of the greatest voices of Tango: Roberto Rufino, Alberto Podestá, Jorge Durán, Oscar Serpa and Carlos Acuña.

"Di Sarli always avoided the extremes of the evocative traditional tango and the avant-garde, preferring to forge his own style without concession to the fashions of the day."

Learn more about Carlos di Sarli: